California counties, including Santa Clara and San Mateo County, have declared war on the Yellow Fever Mosquito. The battle against this mosquito began last summer at the Holy Cross Catholic Cemetery in Menlo Park, and is ongoing.

This mosquito, as an adult, is recognizable. It is a small, black and white mosquito, about one-fourth of an inch long that bites most often during the day, according to the San Mateo County Mosquito and Vector Control District.

Kim Keyser, a biologist with the district, collected the first specimen from the Menlo Park cemetery last August. Her team stumbled across this species in the larval form: “When we found the mosquitoes, they were eggs. We reared them as adults in the lab and were positively able to identify them as the Yellow Fever Mosquito,” Keyser said.

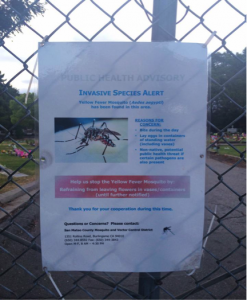

Following this verification and discovery, Keyser and her team performed door-to-door inspections in Menlo Park neighborhoods in the hunt for this uncommon and invasive species. The California Department of Public Health (CDPH) is working with local agencies to control the spread of these mosquitoes and to raise public awareness.

This Aedes aegypti species is not native to California, but has been found in limited areas of San Mateo, Fresno, Madera and Los Angeles counties.

According to Russell Parman, acting manager of Santa Clara County’s Mosquito and Vector Control District, “The problem with these mosquitoes is that they hitchhike in various kinds of ways.” Parman explained that reported cases of the diseases carried by this species in Santa Clara county are not due to local mosquito transmission.

The two primary and most concerning diseases spread by Aedes aegypti are the dengue and chikungunya viruses. These diseases, which cause fever, headache, muscle and joint pain, are efficiently transmitted in a cycle — mosquito, to human, and then back to mosquito.

CDPH is not sure how this species was introduced into California. The department of health said that it likely happened via the mosquito eggs, which can survive for months on objects such as tires, plant pots, cans or bottles, as they were imported into California from an infested area. It is also possible that this species arrived via individuals traveling to areas where these diseases are endemic.

This potential killer, which is considered a “container-breeder,” can reside and breed in any natural or artificial water container, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

According to the CDC, plotted plants and bases, small buckets, plants in water, animal drinking bowls, pools, discarded bottles and tires are among items left outside that accumulate water and give this disease-carrying vector a proper breeding ground.

The mosquito life cycle — from egg, to larvae, pupae, and to adult mosquito — is completed in eight days and the adult mosquito lives for approximately one month. Female mosquitoes lay dozens of eggs up to five times during their lifetime.

“This species takes multiple blood reels from multiple victims before they lay their eggs,” said Parman. According to Parman, female mosquitoes start feeding on humans to ripen a new cycle of eggs, potentially infecting various individuals. Egg production sites are within or in close proximity to households, according to the CDC.

“Feel free to report this a dozen times,“ Parman said, “The more times we repeat the homeowner responsibility to find small water sources and eliminate them, the better.” These mosquitoes do quite well as long as they have a human microhabitat with lush vegetation, Parman explained.

In an effort to combat the spread of this species and eradicate it, public health officials have turned to educating the public on this issue. Press releases, door-to-door inspections, billboards along Highway 101 and the distribution of approximately 18,000 flyers throughout the Palo Alto area are among some of the measures being taken to educate the public according to health officials.

Parman said, “It is really all about notifying the vector control districts.” He claimed that if the public is educated enough to detect these mosquitoes at an early stage and notify health officials, there is a chance of eliminating the species completely.

If individuals are bitten by mosquitoes during the day, they should contact their local vector control agency to inspect their property for Aedes mosquitoes. Most mosquitoes in California do not bite during the day, according to the San Mateo County Mosquito and Vector Control District.

CDPH is providing ongoing consultation to the affected counties and requesting that all vector control agencies enhance surveillance for this invasive Aedes aegypti mosquito. More serious measures include the deployment of mosquito traps for surveillance in affected areas of the county. According to San Mateo County Mosquito and Vector Control, these traps attract adult mosquitoes with water and oat grass mixture.

Mosquitoes stick to the edges of the trap lined with sticky glue and this allows the mosquitoes to be detected. Parman confirmed that there are currently 63 of these traps in the field in Palo Alto and throughout the rest of the county.

Early detection and control increase the possibility of eradication. According to CDPH, in the three counties where Aedes aegypti have been detected, these mosquitoes have persisted since last year and current control efforts focus on reducing mosquito numbers and containing the spread.

The CDPH and vector control districts urge residents to take extra precautions to prevent mosquito bites, including wearing mosquito repellent, long-sleeved clothing and ensuring that there are intact screens on doors and windows. People should dump water from containers on their property and change the water in birdbaths and pet bowls weekly. “It really is all about the water,” said Parman.

He further added: “We don’t want this species to be established here. This is a game changer in terms of the quality of life.”

In her concluding remarks, Keyser said: “We are still going door to door trying to get access to every property in the affected areas. We continue to revisit houses requesting that residences be mindful of watering.”

“Keep it dry, please,” Keyser requested.

Homepage photo courtesy of U.S. Department of Agriculture via Flickr.