Alarmed that several Victorian-era houses have been destroyed or are slated to be demolished to make room for new development, Redwood City officials are exploring ways to protect historic homes in the city.

Councilman Ian Bain said any new plan might not save properties already slated for demolition, but could help preserve similar properties in the future.

In one such case, a Queen Anne Victorian house near downtown is being offered on sale to the public for 90 days starting Oct. 20 for a dollar as protocol before it is demolished to make way for a seven-story apartment building. If someone does buy the house, which is a designated historic site with low-level protections, they must pay to relocate it.

Bain, disturbed by the case of the one-dollar house, diverted from the scheduled agenda of pay raises and beautification efforts at an Oct. 6 city council meeting, to address what he sees as an urgent problem that needs the council’s intervention.

“This is one of many houses like this that is considered historic, but not considered having enough historic significance to save,” he said.

“These homes are becoming more and more rare, and once they’re gone, we lose part of the history and the character and the charm of Redwood City.”

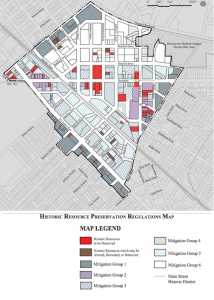

While the council couldn’t formally discuss the topic because it wasn’t on the agenda, Bain asked members to consider temporarily relocating such homes to nearby lots owned by the city. The city’s Downtown Precise Plan identifies seven historic structures within the downtown area as possible candidates to be altered, relocated or removed, though the Queen Anne is the only one in imminent danger.

Mayor Jeffrey Gee acknowledged the importance of finding a solution, but warned that moving houses could be costly for the city.

“Beyond the temporary move, the big question is what do we do with them after?” he asked. “If we wind up owning [these homes], there’s a financial cost to that.”

The city recently bought a house built near downtown in 1882 that was assessed as beyond repair. It hopes the land on which the house sits could be used to expand the neighboring children’s park, Jardín de Niños. The city is currently undergoing California Environmental Quality Act checks on the property to determine its options.

In another case, the city is pursuing a $10,000 fine against what it described as an “overzealous” homeowner who demolished a similar home without permits while attempting to modify the structure.

Bain identified the Centennial and Stambaugh-Heller districts — directly adjacent to downtown and home to many old buildings — as particularly at risk. Some structures in these districts date back to between 1860 and 1880.

Stambaugh-Heller, intersected by bustling Middlefield Road and the Caltrain tracks, is rarely quiet. The mostly low- to middle-income neighborhood contains several meticulously maintained Victorian homes, some of which sit directly across the street from crumbling cinderblock apartment buildings. The district also contains old structures that do not have historic protections and have not fared so well, with dilapidated facades and dead lawns.

Bain hopes that possibly relocating structures with historic protections to the neighborhood may help to beautify it and encourage others to come in and renovate the district’s existing Victorian-era buildings. Homes from this period often do not get historic protections unless they can be linked to an important person or event in history.

Moving a small historic house to a new lot can be costly. To relocate a house like the Queen Anne Victorian to a nearby location could cost anywhere between $15,000 and $40,000, estimated Gabriel Matyiko of Expert House Movers, a company that specializes in moving historic structures. It is unclear who would pay for the moves of such houses if the city commits to saving them.

The cost of repairing such a building and bringing it up to code after the move is even more difficult to determine. Bain is hoping the city may be able to recoup costs by selling the homes at a fair market value, or that members of the private sector might help with some of the work.

“Developers have a real opportunity here to step up and help us out,” he said.

Community involvement in saving these historic homes would not be unprecedented on the Peninsula. When a dilapidated San Jose Victorian home linked to local painter and photographer Andrew P. Hill was slated for demolition, the Victorian Preservation Association of Santa Clara Valley (VPA) was able to acquire the structure and move it to a new location.

“If you’ve ever lived in an old home, you realize they have an entirely different character from a new home. Most of this comes from its history and from the families that have lived there,” VPA member Matt Knowles said. “They are our history and they are not reproducible. Once they’re gone, they’re gone.”