After years of environmental lobbying, plastic bags are on their way out in Sunnyvale, one of many communities in California ditching plastic in favor of paper and reusable bags.

After years of environmental lobbying, plastic bags are on their way out in Sunnyvale, one of many communities in California ditching plastic in favor of paper and reusable bags.

The Sunnyvale City Council approved an ordinance in December banning single-use plastic carryout bags for grocery stores, convenience stores, and other large food and drink retailers, but not for restaurants and nonprofit organizations. Until spring of next year, stores with less than 10,000 square feet of retail space are also exempt.

Nine other cities and counties in the region have proposed or adopted similar plastic bag bans. Beginning with San Francisco in 2007, the Bay Area has been one of the most heated battlegrounds in a plastic war, pitting environmentalists against industry representatives, who pitch themselves as defenders of truth.

Sunnyvale’s ordinance doesn’t go into effect until this summer, but locals are already getting ready. Chris Iguchi, manager at the Trader Joe’s in the Sunnyvale Shopping Center, said sales of the store’s reusable cloth bags have doubled since Jan. 1.

State law prevents Sunnyvale from allowing merchants to charge for plastic bags. So, starting on June 20, customers will have to choose between bringing reusable bags and buying 10-cent paper bags. The paper-bag fee will increase to 25 cents in 2014, part of a countywide goal to encourage mass adoption of reusables.

That goal is recycled from Save the Bay, a nonprofit environmental group based in Oakland. Allison Chan, a Save the Bay lobbyist who focuses on pollution caused by bags, said she oversaw a research and outreach campaign in Sunnyvale before drafting a potential version of the ordinance last year and sending it to the council as they began their deliberations.

Chan said she advises cities and towns seeking to get rid of plastic on how to avoid legal challenges. Under the California Environmental Quality Act, pro-plastic groups sued to stop a similar ordinance in Oakland, because the city had not publicly studied what environmental impact the proposed changes would have. The success of that lawsuit prompted an environmental impact report in San Jose not long afterwards.

Along those same lines, Sunnyvale appointed a seven-person sustainability commission from a pool of outside applicants and gave it two tasks: completing an environmental impact report and recommending what action the council should take. One of the commissioners, Barbara Fukumoto, said the commission was “strongly in support” of the ordinance.

She added that the commissioners had “minimal, if any” direct contact with Save the Bay.

However, Fukumoto acknowledged that the sustainability commission and the City Council faced challenges from industry lobbyists like Manny Diaz from the American Chemistry Council and Stephen Joseph from the Save the Plastic Bag Coalition.

Joseph declined to discuss the specifics of his organization’s contact with elected officials.

Fukumoto said Diaz, a former San Jose councilman, spoke out against the ban at a public council meeting, and Save the Plastic Bag “commented extensively” on the impact report.

“Hundreds of pages had to be inserted,” she said.

Joseph, who represents the bag industry, pressured the commission to acknowledge in its impact report the alleged environmental dangers of using more paper bags, but the council declined to amend the report in response to his allegations.

Save the Bay counts Joseph among its most persistent opponents across the region. He challenged Save the Bay’s widely promoted estimate that at least 1 million plastic bags enter the San Francisco Bay every year, alleging that the group fabricated the number to drum up support.

“Environmentalists will say anything,” Joseph claimed. “Not all of them, but many campaigners don’t feel any constraints. They make up statistics” and “just pull them out of a hat.”

“There’s no support for” Save the Bay’s million-bag number, he added. “They just made it up.”

Chan said Save the Bay derived its estimate from data provided by the California Coastal Commission, a state agency that oversees an annual Coastal Cleanup Day. The commission counts and records what types of trash volunteers remove from the waters.

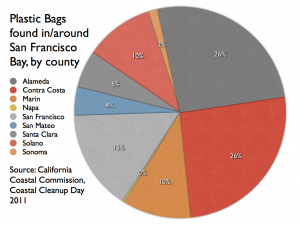

Data provided by the Coastal Commission shows that on Sept. 17 of last year, volunteers collected 30,525 plastic bags from the dozens of cleanup sites in all nine counties around the Bay. Santa Clara County was the third least polluted of the counties, accounting for less than 6 percent of the bag total.

Shannon Waters, a program assistant at the Coastal Commission, said that based on the Cleanup Day data, Save the Bay’s estimate is reasonable.

Chan said Save the Bay calculated its estimate by taking the bags collected on a previous cleanup day as a representative sample of the 29,000 miles of Bay shoreline and connected creeks. That math yielded a total of nearly 2 million bags, so “‘1 million’ bags in the bay is a conservative estimate,” she said in an email.

Both Chan and Joseph said local residents could find proof for their opposing arguments by looking at the waters from the land, wherever they are.

“There’s always going to be caveats to data,” Chan said. “But aside from all of that, if you just go out into our creeks or go out on the shoreline, you will see plastic bags. And there’s no denying that.”

Joseph had originally pledged to sue Sunnyvale and six other California communities, as well as Santa Clara County, while their bag-ban ordinances were still under legislative review. However, he said the coalition has since changed its focus to communities that, unlike Sunnyvale, are not armed with environmental impact data.

Sunnyvale is “so small that it just really doesn’t matter,” he added.

Chan counters that the plastic bag ban in Sunnyvale is only an early step in Save the Bay’s eyes. Palo Alto, San Jose, and the unincorporated areas of Santa Clara County already have bag bans on the books, but Chan said her organization hopes to see a statewide ban in the coming years — “the sooner the better.”

She said the ordinance “will provide the example that’s necessary for other cities” to be able to say, “’we can move forward, too.’”