Santa Clara County is urging residents to be on the lookout for an exotic, bloodthirsty tiger with a potentially lethal bite. It was last seen in Los Angeles County on Dec. 28.

Asian tiger mosquitoes are a much smaller threat than jungle cats and haven’t been linked to any human illnesses in California. But officials aren’t taking any chances. Once the species becomes established, it is very difficult to eradicate and can spread diseases such as chikungunya, dengue fever and encephalitis.

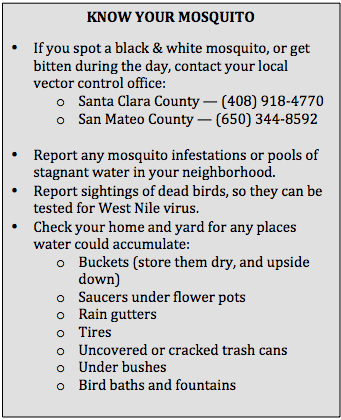

The county is launching a public education campaign, asking residents to “be our eyes and ears,” said vector control chief Russ Parman, who will oversee the effort. The tiger mosquito is easily distinguished from common local species, due to its distinctive black body with white stripes and aggressive biting during daylight hours. Parman’s office is also laying simple water traps across the county and using helicopters to locate stagnant pools of water where mosquitoes might be breeding.

The best way to eradicate invasive pests is to catch them early, before they can reproduce and branch out. In early September, officials in Southern California began getting calls about strange-looking, day-biting mosquitoes east of downtown Los Angeles. They went door-to-door and sprayed to suppress the insects, but “there were quite a few of them out there” and it’s impossible to know whether any larvae survived, said Kelly Middleton, a spokeswoman for the San Gabriel Valley Mosquito & Vector Control District.

With warm weather following recent rains, spring is a prime time for the invasive pest to reappear.

Tiger mosquitoes don’t need a large water source to propagate. “A bottle cap under a bush filled with water — that’s enough,” Middleton said. Their larvae can also survive periods of drought. So if a homeowner dumps out a bucket of water and it remains dry until the next rain, dormant larvae left over from the original water could start growing again, she said.

“If the bug is established in Southern California, then it changes the game,” Parman said. “It wouldn’t make sense for us to talk about trying to eradicate — just prepare for their arrival.”

“If the bug is established in Southern California, then it changes the game,” Parman said. “It wouldn’t make sense for us to talk about trying to eradicate — just prepare for their arrival.”

A resurgence of tiger mosquitoes wouldn’t create an overnight epidemic. But if they go unnoticed, the insects could “hopscotch all over the state, slowly but consistently,” Parman said.

Tiger mosquitoes took hold in Texas after arriving on shipments of tires from Japan in the 1980s. They spread across the South and as far north as New Jersey, becoming “a persistent day-biting menace and extremely costly to manage,” Middleton’s office wrote in a March 14 public information alert.

William Reisen, director of the Center for Vectorborne Diseases at UC Davis, said the tiger mosquito is a threat to lifestyle as well as public health. They are so pesky and aggressive, it would “definitely change how everybody spends time outside of their homes,” he said.

Recently, the species has helped spread chikungunya from eastern Africa to India and even Italy, Reisen said. A few million people have contracted the virus, which causes fever, muscle pain, nausea, rash and joint pain. Reisen is also concerned about transmission of the dengue fever virus, which can be fatal and occasionally shows up in California when travelers return from abroad.

California’s first encounter with the tiger mosquito was in 2001, when the insects came through the ports of L.A. and Oakland on shipments of bamboo from South China. Parman said inspectors were able to stamp out those populations early.

Officials don’t know the source of the latest infestation, which covered about 18 square miles of mostly suburban neighborhoods. Middleton said they are a different strain from those in Florida and Texas — possibly a strain from China. They could even be “a remnant from the 2001 introduction that finally took hold,” she said.

The tiger mosquito is more dangerous to humans than native species, mostly because “it can transmit other diseases that we haven’t had to deal with before,” Middleton said. “That’s the big problem with people and cargo being so mobile now. You can get any insect, any disease, any day.” It’s a threat less flagrant than a pouncing jungle cat, but one that is more likely to come to pass.