The downtown Redwood City of yesteryear earned a crude nickname: “Deadwood City.” But since the 1980s, a steady stream of redevelopment funds paved the way for a new breed of restaurants, movie theaters and shops that continue to draw large crowds of residents and visitors alike.

Now, city officials say, the progress is at risk of stalling.

Gov. Jerry Brown’s proposed 2011-12 budget calls for eliminating the 399 redevelopment agencies in California and rerouting $1.7 billion of local property-tax revenue the agencies would have captured. The money would go to local public schools to make up for budget gaps the state has been filling for years.

The fate of redevelopment agencies now rests with California’s Supreme Court. By Jan. 15, the court is expected to decide two questions: Is it constitutional to eliminate the agencies? And if so, does the state have the power to ask the agencies to voluntarily pay $400 million a year to stay functioning?

A ruling in favor of the state could have enormous impact on cities.

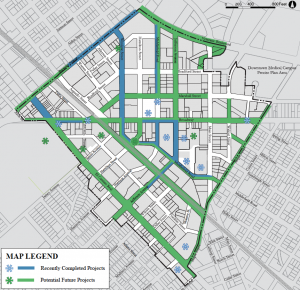

In Redwood City, more than $50 million in redevelopment funds have already helped spur the downtown revival. Yet several multimillion-dollar projects remain on the drawing board. They include creating an elaborate traffic circle (dubbed “Depot Circle”) to bridge the Caltrain station to the city’s downtown and commercial hubs, and also turning attention toward redevelopment along El Camino Real.

Without a redevelopment agency, city officials say, there would be no obvious source of public funding, and developers might shy away as a result.

“If you’re relying solely on the private market to jump in, it gets too easy for them to go someplace else,” said Bill Ekern, Redwood City’s director of community development.

California has a long history with redevelopment agencies, beginning with their creation in 1945. For decades, the agencies were hardly noticed. But after voters approved Proposition 13, the state’s 1978 anti-

tax initiative, they gained prominence as a new revenue source that cash-strapped cities could tap.

Once a redevelopment agency designates an area “blighted,” local property taxes are frozen at current levels. Moving forward, the agency then receives tax increment dollars from the improvements to the area, which can be extremely lucrative.

Joe Mathews, a longtime California journalist, said redevelopment has been used as a “workaround” to Proposition 13 in many cases. “There’s no good or bad in this,” he said. “I mean, it’s just the state and the locals, in a system that’s completely broken, trying to do the best they can … and trying to grab what money they can grab.”

Even if redevelopment agencies go away, Mathews predicts that other workarounds will rise in their place.

“We’re at the point in the movie where the budget machine is kind of killing us, and there is nothing we can do about it,” said Mathews, a senior fellow at the New America Foundation.

In cities across California, the agencies have been important funding sources for affordable housing; 20 percent of redevelopment funds are required to be used toward affordable housing initiatives.

Phillip Kilbridge, executive director of Habitat for Humanity Greater San Francisco, said redevelopment agencies have been valuable partners in approximately 75 percent of his organization’s projects — by helping with financing, purchasing land or addressing other community needs. With the support of Redwood City’s agency, Habitat for Humanity has built 51 homes, including projects on Rolison Road, Lincoln Avenue and Hope Court.

With their futures uncertain, redevelopment agencies are sitting on the sidelines for now, resulting in a standstill for new projects, Kilbridge said.

“We were working on a deal to build somewhere in the order of 14 … homes in Redwood City and were making pretty good traction on it,” he said. “Then all of a sudden we haven’t been able to talk about it for a year.”

Entrepreneurs who came to Redwood City because of the city’s development efforts are hoping the momentum will not slow.

Retail business co-owner Kirsten McKay said she and her two business partners saw an opportunity to open their home furnishings and accessories store, Brick Monkey, in the refreshed downtown. “We thought that this was kind of a place that was rejuvenating and had opportunity for a new store to come in and kind of be on the vanguard as opposed to going to a place that was … completely already developed,” McKay said.

While it may be ideal to get more redevelopment funds, McKay said, the city has laid a good groundwork for businesses to continue coming in. Companies such as YuMe, Equilar and Turn all have their headquarters in Redwood City.

“I realize times are tight and the state is suffering, and there is a limit to how much you can take the existing pool of funds and spread,” McKay said.

Jim Kennedy is interim executive director at the California Redevelopment Association, an organization whose membership includes 357 of the state’s redevelopment agencies. Kennedy argues that the proposed elimination of redevelopment agencies, and the state’s voluntary payment plan, violate provisions of Proposition 22, which voters passed in 2010. The measure stipulates that California cannot take funds from local entities to balance the state’s budget.

The state sees the debate along different lines. The deputy director of California’s Department of Finance, H.D. Palmer, said redevelopment agencies were created by the legislature and similarly can be dissolved by the legislature.

Palmer also questioned whether redevelopment agencies are as important as some believe. “The private development that occurs in redevelopment project areas in our view often … would have occurred, even if the RDAs (redevelopment agencies) were never established,” Palmer said.

The nonpartisan California Legislative Analyst’s Office (LAO) agreed. In its February report on whether California should end redevelopment agencies, the LAO found inefficiencies in the agencies’ use of funds for affordable housing and no evidence that agencies’ initiatives led to increased economic activity.

The report concluded by agreeing with the governor’s proposal, but stipulated that the revenues diverted from redevelopment agencies should simply be treated as property taxes.

If the state wins the legal fight, agencies could stay in the game through what’s being called “voluntary alternative redevelopment.” To do so, however, they would have to collectively pay $1.7 billion in the 2012 fiscal year and $400 million dollars a year going forward.

Some opponents of this idea are calling it a “ransom payment.” But in Redwood City, Ekern said, they plan to “pay to play” if needed.

[youtube]pabyxvsMicQ[/youtube]