This piece is an extended version of an article published in conjunction with the San Francisco Chronicle and its website, SF Gate, where reporter Erchi Zhang is an intern.

When Jeff Bollengier and Richard Stump founded their Bay Area company in 2008, they dreamed of revolutionizing the way people eat. Simple Wave makes a bowl that introduces an inward-curving lip to guide food back onto the spoon and help prevent over-the-edge spills.

But when it came time to choose where to manufacture the bowls, the co-founders followed the pack and opted to outsource production to a factory in China. “We basically did what we thought everybody else did,” Bollengier said.

Not any more. In September 2011, Simple Wave decided that its product, called a Calibowl, would be manufactured entirely on U.S. soil, joining a small but growing effort to shift manufacturing of American-owned goods back home. President Obama promoted this trend as “insourcing” in his January State of the Union address. Others use the term “reshoring” or “onshoring.”

Across the country, businesses ranging from Master Lock in Wisconsin to Chesapeake Bay Candles in Maryland to Sleek Audio in Florida recently moved all or part of their production process to the United States. Last week, the New York Times reported that Google would assemble its new media player, the Nexus Q, in a San Jose factory and have the words “Designed and Manufactured in the U.S.A.” etched into the device.

It is difficult to quantify the impact of these developments. When the nation’s economy slowly began to recover, companies opened new plants for various reasons, and reshoring was just one of them. “There is a lot of talk about reshoring in recent years,” said Eric Appelblom, vice president of sales at Jatco, the Union City-based plastic molding and injection company that makes the Calibowl for Simple Wave. About six months ago, Appelblom said, he started to see reshoring go “from idea to reality.” (Article continues below)

[youtube]U8xD_aGyP7o[/youtube]

Increasing salary levels at Chinese factories, a stronger Chinese currency and soaring oil prices all contributed to a resurgence of U.S. manufacturing in the past three years. But while the trend has gained a lot of attention from company executives, a number of obstacles remain. Among them: Community colleges in many states abolished their manufacturing programs over the past decade or two as more jobs went overseas, which now creates a job training vacuum; there’s a shortage of skilled workers across the country; and the training of new workers has become a financial burden for small companies.

In California, the state with the largest number of manufacturing jobs, companies have long complained about strict environmental regulations and high taxes and labor costs. All of those factors, executives say, make reshoring even harder.

Appelblom said reshoring didn’t “create” new jobs for his company, but rather “replaced the jobs that were lost previously to Asia.”

He described the ideal product for reshoring as “very simple, not labor-intensive,” capable of being manufactured automatically and targeting the U.S. market. In other words, “not for iPhones,” Appelblom said.

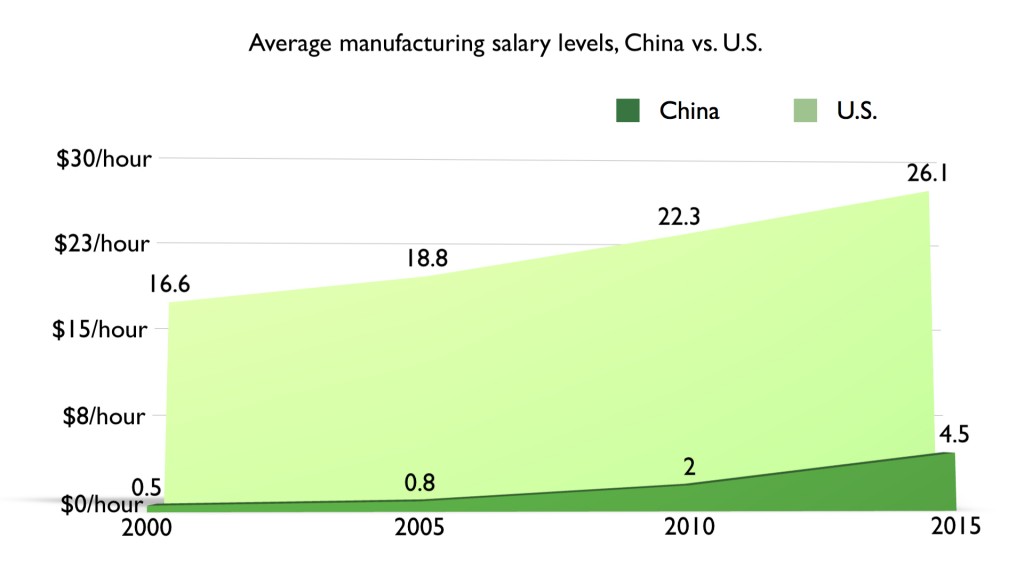

That explains why total cost, instead of production cost, is repeatedly mentioned in conversations about reshoring. Although wage levels for average Chinese factory workers are increasing by 15 to 20 percent per year, according to a Boston Consulting Group report, the hourly salary is expected to be $4.50 in 2015, or 17 percent of that in the U.S..

Labor usually accounts for about 7 to 25 percent of the production cost, the report said. Total cost factors in other considerations such as shipping expenses, inventory, the risk of natural disaster and even the potential for intellectual property theft. Emphasizing total cost, the report concludes that by 2015 the expense gap between outsourcing to China and manufacturing in some southern states, such as South Carolina and Alabama, will be minimal, if the products are made for the North American market.

On the other hand, the report said companies that make mass-produced, labor-intensive products, like shoes, are unlikely to head home, favoring Vietnam and other low-cost nations in Asia if they decide to leave China.

But those low-cost nations will not be able to absorb all the jobs that are likely to leave China, the report said. China has around 215 million industrial workers, approximately 58 percent more than the industrial workforce of Southeast Asia and India combined.

California did not make the list of “low-cost states” in the report. The average annual salary for all employees of manufacturing companies in California was $53,200 in 2009, 21 percent higher than their counterparts earned in South Carolina, according to Census figures compiled by the Department of Commerce. Still, Appelblom said California has advantages over other states, notably that products can be easily delivered to anyplace on the West Coast without skyrocketing transportation expenses.

Bollengier described Jatco, his new East Bay manufacturer, as a “perfect fit” for both Simple Wave and himself. His office in Hayward is five miles from Jatco’s headquarters in Union City. Relieved from the inconvenience of flying to China and “baby-sitting” the quality of overseas production, Bollengier said he now visits the site every other day. He said he also shares a passion for surfing with Appelblom, who is about the same age.

Overall, Bollengier said, he is pleased with having the products manufactured “right in the backyard.” But not everyone agrees.

“The worst state for business”

For eight consecutive years, California has been ranked as the “worst state for business” by Chief Executive Magazine, based on a survey of more than 500 CEOs. The criteria ranged from taxation and regulation to workforce quality and living environment; states with higher taxes and more rules for businesses tend to rank lower.

California “is a fairly unfriendly state for manufacturing because the cost is one of the highest in the country,” said Hank Holzapfel, president of the Corporation for Manufacturing Excellence, a consulting firm that assists Northern California manufacturing companies. When it comes to reshoring, Holzapfel said, states with lower salary levels and tax rates, as well as looser regulations, have an edge in attracting companies that move back.

“The state that’s usually ranked best is Texas,” said David Beach, co-director of the Stanford Alliance for Innovative Manufacturing at Stanford University. Beach said the Chief Executive Magazine ranking reflects the opinion of the manufacturing community on regulation, but “you cannot have millions of people living in a place without a government.”

California needs to find a way to be more friendly towards manufacturers, but that doesn’t mean “to end regulation and all taxing,” he said.

On March 21, executives from throughout Northern California gathered in Santa Clara for the Silicon Valley Manufacturing and Technology Summit organized by the Corporation for Manufacturing Excellence.

Having met with Holzapfel in Sacramento on a previous occasion, Harry Moser was invited to give a presentation on reshoring at the summit. Founder of the nonprofit Reshoring Initiative in 2010, Moser has been lobbying corporations, industry associations and the U.S. government to bring manufacturing jobs back.

Moser was among 19 business leaders who attended the White House “Insourcing American Jobs” Forum on Jan. 11, when Moser said he tried — unsuccessfully so far — to persuade the president to change the word “insourcing” to “reshoring.” He said “insourcing” is not an appropriate term because a lot of American companies, even when they moved back, still “outsourced” their productions to local manufacturers.

After Moser’s speech at the Santa Clara event, a panel discussion quickly shifted to the difficulty of recruiting highly skilled, dedicated workers. From company after company, executives complained about the lack of basic engineering skill-sets among job seekers.

Fred Gapasin, vice president of operations at Giga-tronics, which makes microwave components and signal generators in San Ramon, said he was looking for technicians who could repair the machines used by his company, but found the skill “a dying art” in the United States. He said the technicians he has now were trained two decades ago and are approaching retirement. Unable to find enough new technicians, he said his company is considering a move to Singapore because that is where his competitors are based.

“It is hard to find any community college that’s doing manufacturing programs right now,” Mission College President Laura Jones, a panelist that day, said in an interview. Due to decades of offshoring, Jones said her community college stopped teaching manufacturing skills about 10 years ago. Even if some programs survived, they were likely to be the first thing to go under the continuous budget cuts in California, Jones said, explaining that manufacturing programs are “very expensive” and only benefit “a small number of students.”

In response, Doug Hoffner, undersecretary of the California labor and workforce development agency, said there is funding from the state that companies could apply for to train employees by themselves. “You all pay for it in tax,” Hoffner said during the panel discussion, referring to the employment training tax every employer pays in California.

But trained workers could be hard to retain and expensive to lose. Many job seekers only consider manufacturing jobs as a “stepping-stone,” said Todd Rinella, a panelist and general manager of Corwil Technology Corporation, an integrated circuit assembling and testing company based in Milpitas. He described the frustration of training workers for years and then having them move to better jobs with other companies.

Traditionally, “we have not admired manufacturing jobs,” Beach, of Stanford, said. “Our culture has been characterized manufacturing as dirty, noisy, doesn’t pay very well and doesn’t have much future. Why would there be an education infrastructure preparing young people to go to a field that their parents think is inappropriate?”

Those who survived

Barbara Roberts calls her company a “survivor.” Unlike most of its U.S. competitors, Wright Engineered Plastics — an injection molding, tooling and assembly factory — chose to compete with Chinese manufacturers and kept the work in Santa Rosa.

Roberts said some companies started to see the drawbacks of off-shoring. “What was happening was companies that should never have gone overseas went overseas, because they thought that was the only way to do it,” Roberts said. Now, several have begun to consider whether off-shoring “make sense” to them, she said.

She said she first had a client who decided to move back from China and outsource the production to her company in 2007. Shipping across the Pacific often takes around 30 days and Roberts said local manufacturers like hers could help small business react faster.

Esmeralda Nuno, a manufacturing technician who joined Roberts’s company in 1997, has witnessed a series of changes in the factory. Wright Engineered Plastics bought its first machinery in 1998, and the machines have gradually taken over most of the production work. Although the factory still operates 24 hours a day, there is no need for a night shift anymore. The machines run all night long without the monitoring of employees.

Workers like Nuno worked on production lines before, but have shifted to quality-control jobs now.

“The old style is gone,” Roberts said when she described the current strategy of competing with “a low labor rate market.” She said her company used to have “a very few higher paid” people and “a lot of minimum wage people.” Now, with fewer workers, everyone in the factory moves to the middle- or high-income level.

Between 2000 and 2010, the United States lost about 5.9 million manufacturing jobs, according to a recent report released by the Brookings Institution, a nonprofit public policy organization based in Washington, D.C. The resurgence of U.S. manufacturing in the last three years only brought back about 350,000 jobs in the industry, the Brookings report said.

Statistics are not available on the number of jobs created by reshoring, but even Moser admitted that they only account for “a meaningful but small percentage” of all the jobs added recently.

On the other side, “reshoring would have very limited effect on China,” said Mao Yanhua, a professor studying economics of the Pearl River Delta, a major manufacturing center in China, at Sun Yat-sen University. Although foreign investment remains vital to the Chinese economy, Mao said China has shifted its focus on attracting investment from quantity to quality.

The new focus is to attract research and development centers, high-tech and high-end manufacturing industries, he said. The companies that reshored are not necessarily the ones China is eager to keep, Mao added.

There is one thing China cannot deliver — the “Made in the U.S.A” brand.

About half of the Calibowls are sold to customers from South Korea, Australia, Singapore and other countries. Some clients specifically ask for “Made in the U.S.A” products, Bollengier said. And his company, Simple Wave, promotes that brand on the Calibowl website and in the package of every product.

Bollengier said years of thinking “margins, margins, margins” in the United States have caused many companies to lose sight of the value that associates with American products: quality and innovation.

Holzapfel agreed that making decisions on price makes companies short-sighted. “If you look individually at each company, and they make a purchasing decision based solely on price, that’s where we went (in the direction of) offshoring,” Holzapfel said. “Collectively, on the societal level, there is a cost in unemployment as well, and we pay that in social service.”

Bollengier first met Moser in Chicago in 2011 and was inspired by his “game changing idea.” One year later, Moser uses Simple Wave as an example of how reshoring brought back jobs to the United States.

“(Reshoring) is inevitable,” Bollengier said, predicting a snowball effect once more companies try it. “With the labor cost rising in China by the minute,” he said, “I can guarantee you that.”