In an age where “big data” is a Silicon Valley buzzword, people are increasingly bombarded with lots of data that is too complex for them to process. A Silicon Valley company founded by Stanford math professors has emerged to help analysts make sense of it all.

The company, Ayasdi, (Cherokee for “to seek,”) has pioneered a way to help people visualize and digest complex data, from sports statistics, to financial models, to genetic maps.

The company was born out of one of the most arcane areas of mathematics: topology, which is a type of geometry. The link between the past and present is Stanford math professor Gunnar Carlsson, one of Ayasdi’s founders. Carlsson’s programs allow complex data to be viewed in a 3-D structure, which highlights patterns in a more accessible way than an overwhelming spreadsheet or other form of data display.

Ayasdi’s main goal is to take Carlsson’s theories and apply them to real world problems – finding the relationships between certain genes and the incidence of cancer or analyzing what kinds of sports statistics denote a particular playing style.

With other programs, researchers need to know what they are looking for. They can search through big data sets, but they must do so in a targeted way, or have a guess at what patterns may already exist. With Iris, one of Ayasdi’s products, unexpected patterns can be detected, sometimes with enormous benefit.

Iris specializes in finding “a small signal in a noisy data set,” Johnson said. Groups of data can be compared with the push of one button. The statistical significance of a certain event can be perceived in seconds.

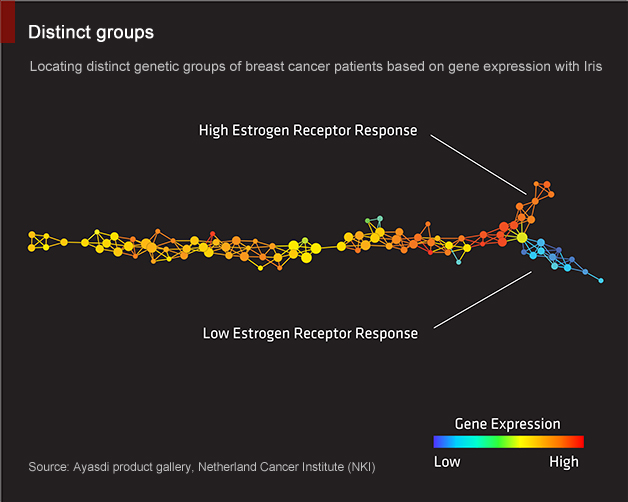

In one example, Iris processed genetic data from 272 breast cancer patients and revealed a sub-group of patients that no one had ever found before. Low estrogen receptor expression in women with breast cancer is usually a sign that those women are more likely to die, but Iris found a group of these low expression women who all survived. Women with similar genetic profiles can now receive targeted breast cancer treatment based on the results of others in their group.

Researchers knew that something interesting might be revealed by looking at the variation in gene expression and comparing it to patterns of survival, but they didn’t know what. Now they have a targeted area to research.

Iris also breaks down the data into smaller pieces for further analysis. In the breast cancer data, Iris separated patients who died into subcategories based on their similarities. Studying these individual groups can help create specific genetic profiles to target patients more effectively, company officials said.

Ayasdi’s main innovation compared to competitors in traditional data analysis techniques is its ease of use. Whereas traditional data analysis programs require knowledge of computer science to be used most effectively, an average researcher or businessperson can become competent in Iris in just hours, according to Ayasdi data scientist Alexis Johnson. The company has customers in the life sciences, sports, retail, telecom, manufacturing, finance, oil and gas, and public sectors.

Ayasdi’s technology will allow scientists and researchers in a variety of fields to perform data analysis themselves rather than hiring computer scientists to do it for them.

Traditional data analysis is limited – it usually compares groups of data points according to a few specific characteristics. Iris uses a 3-D web of lines to show which data points belong to multiple groups, displaying multiple analyses all at the same time.

“Humans are innately capable of recognizing patterns,” said Jeff Yoshimura, Ayasdi’s vice president of marketing. Iris allows users to see all of their data at once in a way that isn’t overwhelming. This allows them to get a sense of what their whole data set looks like, and allows them to recognize patterns without becoming lost in the details.

“If Carlsson and topology stood alone, the technology would sit in research papers,” Yoshimura said. “Ayasdi has real applicability beyond academia or the government… it has moved to the commercialized mainstream.”

Ayasdi was founded in 2008 by Carlsson, Harlan Sexton, and Gurjeet Singh. Sexton and Carlsson met as Ph.D. mathematics students at Stanford in the early ‘70s, and Singh joined the team when he was Carlsson’s math student in 2007. Khosla Ventures, a venture capital firm, invested $10.25 million in Ayasdi in January, allowing Ayasdi to launch their new website and to open an office in downtown Palo Alto.

Carlsson remains a full-time professor in Stanford’s math department and advises Ayasdi. Stanford is “the premier place in the world for all sorts of interdisciplinary interactions,” he said in a phone interview. “I myself have taught at other places. I taught at Princeton before this, and in none of those places is the environment even close to comparable.”