Hear more about this story and how it developed on the Peninsula Report podcast >>

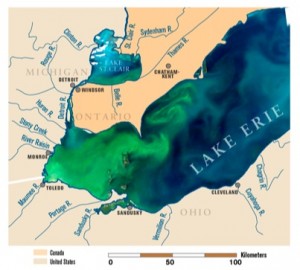

Two summers ago, a nightmarish algal bloom overwhelmed Lake Erie with a toxic scum that suffocated fish and fouled shorelines. A new Stanford University-led study finds that if policymakers don’t implement a management plan quickly, the lake can expect more of the same as the effects of climate change and fertilizer runoff take their toll.

Scientists have seen similar impacts of algal blooms elsewhere, including the marine waters off California’s coast, where agricultural and sewage pollution have helped feed other types of toxic algal blooms. Meanwhile, locals just north of the Bay Area are leading an innovative management strategy to target algal nutrient hotspots so that they can try to halt growth before it starts.

The study was published April 1 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences by a team led by Anna Michalak, an associate professor in Stanford’s Department of Environmental Earth System Science. The researchers identified that weather conditions and farming practices created the ideal environment for runaway algae growth, at the expense of local Ohioans and the lake’s aquatic biodiversity. Similar conditions in the future could lead to more record-breaking algal bloom events of equal or greater magnitude, the report added.

“All these extreme [algal bloom] events depend on a number of factors coming together,” Michalak said in an interview. “There’s a number of things that are trending in the direction of making ideal conditions for these types of blooms more common.”

Without a comprehensive plan to manage the “monumental” algae growth, the authors conclude, “we can therefore expect this bloom to indeed be a harbinger of future blooms to Lake Erie.”

What might this management plan look like? While one Great Lake awaits a meaningful mitigation scheme, more than 2,000 miles away, California officials are pioneering the use of new satellite technology to pinpoint areas of dangerously high, algae-fueling phosphorus in Clear Lake, the Golden State’s oldest and largest lake. Chuck Lamb, a project volunteer and co-founder of Koncocti Regional Trails, helped bring this Blue Water Satellite technology to Lake County, Calif. last fall.

“The problem is that the county has always been in a reactionary mode,” Lamb said. The reality is, managers across the country have addressed algal blooms only once fully fleshed. Now, with the images provided by Blue Water, officials can proactively map the source phosphorus overload and grade its intensity. Most of the phosphorous in Clear Lake comes from sediments due to erosion from agricultural and urban areas, construction, gravel mining and other human activities. Fertilizer use may also contribute to Clear Lake’s phosphorous levels.

Michalak’s study found similar effects in Lake Erie, where farming practices that were conceived out of concern for the environment, like zero-tillage and autumn fertilizer application, had unintended consequences. The researchers observed a 218 percent increase in phosphorus, as well as other nutrients that promote algae growth, running off from farms into Lake Erie’s tributaries. Heavy spring rainstorms and summer heat in 2011 intensified the algal bloom set into motion by these farming practices. These extreme weather conditions are expected to become more common, according to climate change predictions.

Lake Erie is Ohio’s lifeblood. The southernmost Great Lake supplies drinking water to roughly three million people and funnels more than $11.5 billion in annual revenue to the state from tourism, travel and recreational fishing, according to the Ohio Environmental Council. But the super-bloom forced several beaches to close and caused water treatment costs in Toledo, Ohio, to skyrocket by thousands of dollars a day. At the bloom’s peak, the lake’s surface harbored a liver toxin produced by the bloom organisms that may have reached concentrations over 200 times that deemed safe by the World Health Organization.

Jeff Ho, a graduate student in Stanford’s Civil and Environmental Engineering department and an author on the study, remains optimistic. “The sheer magnitude of the bloom is bound to turn some heads and cause some people to take notice,” he said. Just maybe, that attention will lead to action.

Anna Hallingstad, Angela Hayes, Alexei Koseff and Mallory Smith also contributed to this report.

[soundcloud url=”http://api.soundcloud.com/tracks/94646426″ params=”” width=” 100%” height=”166″ iframe=”true” /]