Raja was making a surfboard and the room was covered in foam. It dusted the floor and collected in the folds of the blue tarp on top of it. It was in his hair, too, and on a speaker system playing the dusky, plodding electronica of Darkside.

It ran up his forearms — strong, a climber’s — and some even worked its way out the door of the garage that now plays host to rolls of fiberglass, electric hand planers, jerry-rigged sawhorses, and lots and lots of foam. The music was momentarily drowned out by the squeaky sound of a saw.

The glare from three severe photography lights bounced off his circular glasses as murky drops of epoxy resin dripped onto his feet. He noticed my gaze.

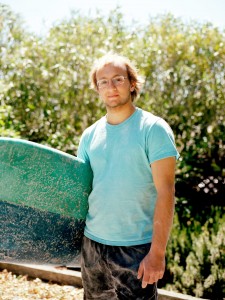

Raja Badr-el-din, the short, squinting man standing before me in an unassuming pair of dark blue shorts, a plain teal T-shirt, and stained flip-flops, was not meant to be into surfboards.

“In order to make surfboards,” he says, “you’ve got to commit a pair of shoes to the cause.”

He has committed far more than that.

He was raised primarily in Jordan, a country blocked almost entirely from the Mediterranean Sea by Israel. Its one coastal town, Aqaba, and the 17 miles of Red Sea coastline around it are best known for being raided by T.E. Lawrence during the First World War. Water sports? Not so much.

After graduating from high school he traveled to the United States to study physics at Stanford. It was any proud parents’ dream, and his were certainly that. Despite the challenges of freshman year engineering classes, there was nothing to suggest he would be anything other than a well-crafted Stanford “techie” ready to make his mark on Silicon Valley.

And then he started making things.

First came skateboards. He bought one and “almost immediately had the urge to build my own.” He started doing so in his dorm room. He transformed it into a tiny workshop and began pumping out the most stylish boards on campus. He sourced sustainable wood and decorated each with his distinctive artwork — a colorful and playful style that toys with the ancient Islamic form of geometric design.

He wanted to make the best skateboard he could. It took 28 tries.

By the 29th they bored him. Each was no longer better than the previous. Quite simply, he had figured them out. And then a group of friends took him surfing.

“We went to Santa Cruz and I was instantly hooked. I was like, ‘oh yeah, there’s something here for me,’” he explains with the goofy grin he gets when talking about his favorite things.

When Raja decides he likes something, he does it a lot. In high school, when it was art, he could spend entire summers holed up in his house, painting. His freshman year of college it was climbing, and he was at the climbing wall or bouldering in the Santa Cruz Mountains virtually every day. “Once I start I want to get it right,” he says. “It’s kind of a slippery slope.”

Now the endearingly bumbling engineer had a new obsession: California’s most iconic of all. But he was tired of renting boards, and his roommate was out of town.

“If I want to get a surfboard why don’t I just shape it? If I can build a skateboard I can build a surfboard.”

“Wrong.”

He took advantage of his roommate’s absence and the dorm room paid the price. Raja was introduced to foam.

“The entire room was white. The floor was white, the walls were white. Foam was all over my roommate’s computer. I was like, ‘oh … can’t be doing this in a dorm room.’”

And the board was useless.

“The rails were wonky. The volume was all off. The fins were really close together and weren’t straight.” He tells the story with only the tiniest hint of embarrassment. “I don’t think I ever stood up on that board.”

There were a lot of problems. But to Raja, the solution was singular.

“I hadn’t spent enough time around surfboards.”

As Raja had come to realize, the creation of a surfboard is a complicated, messy process. It all begins with a big piece of foam. Its deformities must be removed with an electric planer. After that a template is placed on the foam and used to trace the outlines of the board a “shaper” wants to create. Raja designs his templates with a software program called AKU-Shaper.

Templates are what Raja calls “the secret weapon.” He explains that “if anyone gets the template they can just copy it.” Accordingly, shapers are intensely protective of their templates, and to share one with another is a remarkable gesture of trust.

In most professional shops a board is only shaped once and then the dimensions are plugged into a machine that can recreate it. But Raja, who operates off three main templates, is constantly fiddling with his.

Why? “Oh, the tail was sliding out. Or it was too floaty. I could put bigger fins or make it more concave. There’s always 100 ways to solve a problem.”

Once the template is penciled out the foam is cut with a handsaw. Then the electric planer is brought out again, this time to level the foam, which starts at a universal thickness, to the proper distribution. Most boards should be fatter in the middle and grow thinner toward the ends.

Next up for shaping is the rail, which is the phrase for the board’s edges. There is a humor to the terminology of board shaping; though intensely scientific, it is rooted in slang. The rail, for example, must be “floaty” enough, but also “grabby” enough. It can’t be too “skatey” or it might slide away from the wave.

After the rail is shaped, the foam shavings are cleaned off. Graphics, if so desired — and for Raja they almost always are — are then airbrushed onto the foam, along with the board’s dimensions and the shaper’s signature. He places his logo on there too. Mauji Surfboards, Arabic for wave.

At this point there is a good-looking surfboard under the lights. And it’s not yet halfway done.

The board could be shaped perfectly, but if put in the sea as it is now, it would be destroyed by the water and the salt. It needs to be fiberglassed.

Fiberglass in its virgin state comes in big rolls. Light plays on the silver surface as the sheet is laid across the board, making it shimmer in a lunar sort of way. It cut to the rough length and width of the board. Then things get messy. The next part requires gloves.

Epoxy resin is mixed with a hardener — just the right balance or it will be useless by the time it gets on the board. Raja once used a poly resin instead of an epoxy. He doesn’t anymore. “You smell it and feel like you’re dying inside.”

The mucus-like resin is then poured on the board and spread out evenly over the fiberglass. The fiberglass and resin step usually is repeated three times on each side. Though it may seem industrial compared to the art of shaping, Raja considers it the hardest part of the process. It’s critical too — determining the flex, weight, and durability of the surfboard.

Raja does all this nonchalantly, explaining his actions as he works. When he slips up he laughs, handles it, and moves on. He looks assured, and he should be — he’s good. But he wasn’t always.

The dorm room foam incident didn’t put Raja off making surfboards. It just forced him to adapt.

He fiberglassed that first board in the courtyard of Stanford’s political science building. “It was 12 at night. I had to wait not to attract too much attention.”

Fiberglassing, he would learn the hard way, is something best done in an enclosed place. When the resin dried a host of unwelcome visitors, from flower petals to insects, clung to it. But he had nowhere else to go. So he kept working in courtyards, generally in a dubious sort of understanding with his dorm staff.

The fire marshal was less understanding.

“He saw the board drying and the different resins.” That was that. Raja was told to stop.

At Stanford, 97 percent of all undergraduates live on campus. The university guarantees housing for all four years and, given the Silicon Valley pricing of Palo Alto, students take them up on the offer.

In the middle of his junior year Raja moved to Redwood City.

The place he now shares there has all the accoutrement of a dorm room — pizza boxes, beer cans, bags of chips — and one other thing that he is willing to commute 15 miles to class for: a garage.

There are no flower petals in the garage. There are no bugs.

Raja has only been at the house for a few months, but in that time he has filled it with surfboards. Some seem decorative — a wooden one in the corner, for instance — but most of them are just there. The residual of a man honing his craft.

Under meek grins and off-kilter glasses Raja is deadly serious about surfboards. But leaving campus to make them is not something everyone can easily understand.

At school he is seen by many as a sort of a lovable eccentric. Many students might be able to empathize with an obsessive sense of focus. But stories of people leaving campus to pursue something are more likely to include tech startups and huge amounts of money than chunks of foam.

His parents aren’t sure about it either. But Raja has a deal with them as old as college itself. “Just don’t flunk out.”

Like most projects, though, this one costs money. Materials don’t come cheap (about $250 for each board). Nor do tools.

Such is his perfectionism, Raja is hesitant to charge market prices for his boards. I ask how long until he will.

“Five years until I bump my price another 100 bucks.”

My eyebrows rise. He smiles.

“As far as not being able to blame anything on the tools, I’m almost there.”

Up until now he has been able to fund most of the project with cash he has leftover from selling skateboards. He supplements that with money from his allowance. “I buy my books or whatever and then spend the rest of it on surfboards.” The allowance comes from his parents. And though they are all right with him shaping while he is in school, his wish to stay in Redwood City to do so through the summer left them less happy.

“They see a hobby, I see a project. I’m trying to perfect this craft.”

He told me this at a greasy Denny’s table in Pacifica, a beach town just south of San Francisco. Earlier that day he had taken me surfing.

Surfing in Northern California is nothing like surfing down south in Laguna Beach or San Diego. The beach was fogged in, turning the water beneath it grey. A cold northerly wind picked up frigid drops of water from the crests of waves and whipped them across our faces.

But it was beautiful.

Sea lions poked their heads out of the water. Sea gulls dove into it. Yellow wildflowers lined the beach, and evergreens colored the hillsides around it with the reminder that this is not L.A, this is not Hawaii, this is Northern California and things are different here.

Waves broke on inhospitably large slabs of rock that jutted out into the sea from both ends of the cove.

Raja paddled out far ahead of me, and even though he had forgotten his glasses and could hardly see the waves in front of him, I couldn’t keep up.

We chatted for a few minutes once I caught up to him, and then he grew very quiet. He had been so excited to get out there he considered two hours of traffic “so, so worth it.” Now he was totally tranquil.

I had expected him to approach surfing the same way he approached shaping — with the precision and perfectionism of an engineer. But instead of chasing the perfect spot from which to catch a wave, instead of obsessing over the physics of the water, he seemed content to just sit there.

The meditative aspect of surfing is a tired cliché, but for Raja completely true. This was a special thing.

Having seen that, eating pancakes at Denny’s, I understood the anxiety he has for the summer. It is not easy to love something with such limited career paths. And the summer is just a taste of what he will face after graduation.

Taking a break from his Oreo shake he tells me, “I’m not focused on making the most high-performance board. I’m focused on making the board that will make you most stoked to get in the water.”

“Right now it’s about being able to make enough money to pursue those challenges.”

And as he talks about the future I realize that he has no idea what it holds. Few do, I suppose, but the way he spends his time has highlighted the uncertainty of it in a very stark way.

After all, he is in this country on a student visa. Without full employment or an American marriage, it will soon be “goodbye Pacifica.”

Focus can blot out doubt. When he is shaping, or when he catches a wave, Raja’s problems are a light year away. Sitting in the water waiting for one they are less so. Yet in the quiet uncertainty of the moment he is happy.

Maybe, for Raja, it’s all about compromise. This summer certainly will be. He tells me that at his father’s urging he has accepted a Silicon Valley-style internship.

Surfing is not opposed to balance, after all. For every obsessive bum living out of a car there are beaches full of doctors and lawyers and engineers, and they all look the same in a wetsuit.

Floating on his board, I think Raja understands that.

“But the real goal this summer is in the garage.”