Hear more about this story and how it developed on the Peninsula Report podcast >>

SAN JOSE, Calif.—The Bay Area has too many cities and must consolidate operations to improve efficiency and long-term regional health, according to Michael Garvey, former San Carlos city manager.

Speaking at a panel discussion Friday morning at the 2013 State of Valley Conference in San Jose, Garvey emphasized that greater collaboration between municipalities will be essential for addressing the region’s transportation crisis and other looming threats, such as rising sea levels.

“We’re spending a tremendous amount of money on duplicate administrative overhead,” he said. “If every city has to do it on their own, it’s wasteful.”

According to the 2013 Index of Silicon Valley, released this week by Joint Venture Silicon Valley, a regional association of professional and government groups, the Bay Area’s “fragmented system of governance” includes 101 cities and towns and 27 different transit operators in its nine counties.

Emmett D. Carson, president of the Silicon Valley Community Foundation and the panel’s moderator, said a regional focus will be essential in the 21st century Bay Area.

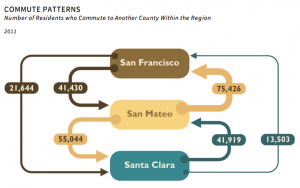

As the distinction between the Silicon Valley and San Francisco has blurred, he said, with people living in one area and working in the other, they must come together to implement new structures that reflect broader communities being created.

“We are witnessing regional identity formation,” Carson said. “People begin to move back and forth freely. They don’t see the boundaries anymore.”

But the major challenge to regionalism could come from those same citizens, who are comfortable with the status quo and fear what broader jurisdictions would mean for their services.

“People want it that way,” Garvey said.

Mark DeSaulnier, a California state senator from Concord, agreed that financial concerns often constrain bureaucratic efficiency and progress.

“We get stuck in a conversation of local government versus regional government,” he said. “We tend to be fairly insular in a group when we’re civically engaged, dealing with our money.”

Instead, those two administrative levels should cooperate to achieve greater political results, he said. The overarching regional government should work to “empower local government, not overpower them.”

DeSaulnier also suggested that the business community could play an advisory role in driving a regional vision for the Bay Area, citing London and Hong Kong as examples.

“It’s ironic that the Bay Area is behind in that regard when other economic powers are looking at us as a model,” he added.

Egon Terplan, a San Francisco urban planner, suggested that the solution might come from an interdisciplinary approach to governing.

“We established these incredible regional entities coming out of World War II, but they were single-purpose entities” focusing on big issues like air quality management and transportation services, he said. “They don’t deal as well with conflicts between them.”

Transportation is especially affected by this narrow view, Terplan said. The lack of a unified public transportation system in the Bay Area has contributed to sprawling conditions that are resistant to change because addressing them would span into other sectors, such as environmental regulation.

He suggested incentivizing different agencies to work together on “cross-jurisdictional threats” like sea-level rise and car dependency.

“We have structures,” DeSaulnier agreed. “It’s how they interrelate and power local communities” that is key.

[soundcloud url=”http://api.soundcloud.com/tracks/79880317″ params=”” width=” 100%” height=”166″ iframe=”true” /]