In perfect, unaccented English, Father Eduardo Samaniego, the Jesuit pastor of Most Holy Trinity Catholic Church in San Jose, recounts his first days in kindergarten. “When I started I could only speak Spanish, and it was sink or swim with learning English. I got made fun of a lot because of my accent and the way I spoke, which was pretty traumatic.”

The eldest of five brothers and four sisters, “Father Eddie,” as he is known by parishioners, was born in Los Angeles. His family emigrated from Mexico before he was born. At 6, he decided he would never be made fun of again for his accent. He practiced every day until he successfully Americanized the way he spoke, and for a time he even Anglicized the pronunciation of his last name.

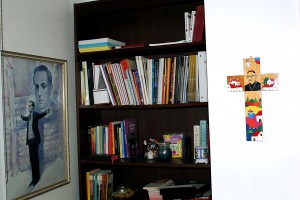

Looking around his current office, it is difficult to imagine Samaniego hiding aspects of his heritage. Crosses decorated with Mexican landscapes adorn the walls. A figurine of a vaquero tops the bookshelf on one side of the window. On the other hangs a painting of Miguel Pro, a Jesuit priest executed by a firing squad in 1927 during the Cristero War.

In 1980, upon becoming a Jesuit, a member of the Catholic religious order Society of Jesus, Samaniego chose to once again view his background with pride.

He has not, however, lost the bigger lesson he learned from his kindergarten shame. “It triggered a soft spot in my heart for those (who) feel unwelcomed or mistreated,” he said.

Battling the banks

In October of this year, after hearing story upon story of foreclosures in his parish, Samaniego translated his compassion into action. He brought the issue to members of the parish’s financial committee, and together they decided to take a stand against large banks. Samaniego announced the divestment of the parish and its school’s accounts, amounting to $3 million, from Bank of America. The money was deposited in a local credit union.

The move came as part of a grass roots, inter-faith community effort in the Bay Area to pressure banks to change their loan modification policies and do more to keep families in their homes.

“We are putting our funds into an institution that we would be proud to be served by,” Samaniego said. “[The divestment] is in solidarity with those who have already suffered the loss of their homes and those who are in danger of losing their homes because of … practices that the banks have found to nickel and dime us to death.”

Realtytrac.com, which tracks foreclosures, reports that Most Holy Trinity’s zip code experienced one foreclosure filing per 271 housing units in September 2011. This is much higher than Santa Clara County as a whole, which experienced one per 441.

Bank of America did not return calls seeking comment for this article. But the bank issued a statement to ABC7 in San Francisco when the television station reported on the divestment.

“We are both sorry and surprised to hear that the church is unhappy, as they have not raised any concerns with our banking center,” the statement said. “Because they cite foreclosure matters as the reason for closing their account, they may not be aware of all the efforts Bank of America has made to help keep people in their homes. This includes having made more HAMP [home loan] modifications than any other lender, and modifying more than 193,000 mortgages in California since the housing crisis began in 2008.”

Politics and finances

When it comes to financial difficulties, Samaniego is no stranger. A few years ago, his parish faced a budget crisis. He had to decide whether to let a staff member go or to cut everyone’s pay by 10 percent.

Samaniego addressed the situation at a Tuesday staff meeting, recalled Mary Jane Araya, who works in the parish’s front office. “He led us in prayer for an answer and then we met with him individually. He helped us reach the consensus to act as a community. We all took the 10 percent cut,” Araya said.

That experience left him with little sympathy for the banks, which he feels do not act in the best interests of their communities. “We all took the cut. Do the banks do that? No. Is it right what they are doing? No,” he said.

When deciding to switch from Bank of America to the Micro Branch Self-Help Federal Credit Union, Samaniego did his homework.

“The nature of our conversations have been very nuts and bolts of how does the parish get an account up and running,” said Haydee Moreno, the Micro Branch director. “I think that is a good thing, because at the end of the day you need a financial institution that will serve your needs. You can be well intentioned, but if you can’t actually provide what needs to be provided, it doesn’t make sense.”

For many parishioners, Most Holy Trinity’s divestment has shed a ray of light onto a dire situation. “It gives the congregation hope, hope that the parish is working for them,” said Pauline Martinez, a local real estate agent and parish member.

This is not the only major change Samaniego has brought about in his nine years with the church.

“He has also increased the participation of the young people. It is really amazing how many more are involved in Sunday mass since Father Eddie became pastor. He really knows how to engage with them,” Martinez said.

Samaniego concedes that his entire parish does not always agree with his liberal stances, such as his opposition to state laws affect immigrants in Arizona and Alabama. “Many of the cultures in the church are politically conservative, and so they just tolerate my preaching on certain kinds of justice,” he said.

Araya and others who work with him, however, believe his fervor has elicited positive change in the church. “His homilies, the way he encourages the communities, really lights a fire in people. I know simply by the increase in donations we’ve seen since he started preaching, let alone his reception by the congregation,” Araya said.

Before Sunday mass a few weeks ago, Samaniego described a concept of justice that caught his fancy.

“I heard a new term the other day,” he said.

“What was that?” replied a young Jesuit whom Father Eddie had chosen to give the homily that day.

“Communionism,” he replied, animatedly gesturing with his hands as he explained. “Capitalism and communism, neither one is an economic system that truly takes care of its people. But communionism, it’s like Jesus. It welcomes all to the table. It is about hospitality, about making sure nobody goes without.”

As every member of the congregation within hearing distance began to enthusiastically nod their heads, loud sounds of agreement echoing from person to person, the young Jesuit smiled broadly. “I like that. I really, really like that,” he said.

Editor’s note: A previous version of this story incorrectly stated that Samaniego was born in Mexico.

Thank You God for you are out there to help home Owner. my question is I live in Orange County California do any community that help me for stop foreclosure of my home

Tien