Teaching children to read and make sense of the symbols in front of them has typically fallen into the domain of education experts and linguists.

Recently though, technology companies have become involved in the process, employing engineers and technologists to design interactive educational, reading toys.

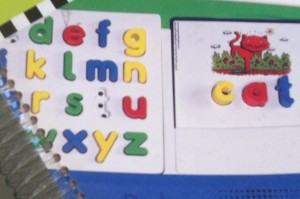

Beginning with its first products in the mid-1990s, Emeryville-based LeapFrog Enterprises ((NASDAQ: LF) has engineered dozens of toys that utilize “sight-sound” technology. On durable, plastic iPad-like devices, children touch a letter and the touch produces the sound of the letter, allowing them to link the two in their minds.

Leapfrog touts the technology, which it first used in the mid-1990s, as the perfect tool for teaching children read skills.

Since the introduction of such technology, however, parents, experts and toy marketers have been involved in a contentious debate about the use of technology at such a young age. While some parents buy their infants iPods and hand over their iPhones as pseudo-pacifiers, others strive to keep gadgets and even television out of sight, arguing that too much technology is not good for developing brains.

From teachers to toy marketers, those in the field of education have weighed in on the role tech toys like those developed by LeapFrog and its rival Hasbro should play in reading instruction.

Stanford education professor Bob Calfee says the process of learning to read is complex, but can be simplified, and technology can help do that. Calfee served as a consultant for LeapFrog after Michael Wood, the company’s founder, approached him in the early 1990s and asked for help designing a toy that would help teach his son to read.

According to Calfee, kids learn to read by learning different syllables, created by pairing a vowel with consonants on either side “like a sandwich.” The vowels serve as anchors, carrying consonants and more difficult sounds like the ‘th’ combination around them as kids learn. The consonants and sounds can then be grouped into longer, more complex words.

After coming across the touch technology in a globe that “spoke” facts when touched, a skeptical Wood asked Calfee what he thought of the idea for LeapFrog.

“I said it was near gold,” Calfee recalled during an interview at his home a few blocks from the Stanford campus. “I said you could put paper on the toy so that it read the page and individual words could interact with the paper, and that technology really led to LeapFrog taking off.”

LeapFrog declined to be interviewed, along with fellow tech toy companies Hasbro and Mattel.

From LeapFrog’s initial Phonics Desk to 2011’s coveted and award-winning LeapPad Explorer, the company has relied on the touch technology that helped catapult it to the top of the tech learning toys market.

Those in the field of education have taken notice, but not all have welcomed the influx of technology in the education sector.

Kumon Corp., a 54-year-old tutoring company headquartered in Japan with learning centers in over 40 countries that focuses on traditional learning methods, conducts reading and writing lessons that emphasize repetition and proper penmanship.

“Our current reading program is worksheet based,” said a spokeswoman for Kumon who did not wish to be identified. “It is individualized and not technology based. The actual putting pencil to paper really creates understanding and we want to make sure students are able to learn concepts to the best of their ability.”

Kumon Publishing, a Kumon subsidiary, recently developed iPad applications focusing on letter recognition. The apps, which are not in use by Kumon tutors, ask students to trace letters and focus on penmanship. They do incorporate touch technology, though. The LeapPad allows children to touch different letters to put together words. The Kumon app, however, prompts children to touch one letter to hear about related sounds and words.

“For us, it’s more about providing a good foundation,” said the spokeswoman.

Calfee, on the other hand, compares learning to read to learning to paint.

“It’s messy and complicated but it should be fun,” he said. “You’re not going to teach a kid all about colors and brush strokes for a year before you let them touch paint. No. You put down a cloth and the paint and let them at it.”

Similarly, he says, learning to read should be fun and interactive. Kids should be able to touch different letters and put them together and take them apart as they learn which sounds do and do not go together.

Calfee was “dismissed” from LeapFrog’s advisory board after then-president and CEO Jeffrey Katz joined the company in 2006.

Described by Calfee as “strictly business and very hard-driving,” Katz was focused on the bottom line. Katz closed down LeapFrog’s assessment and pre-kindergarten to eighth grade curriculum content division, SchoolHouse, because it was not performing well, said Calfee, who supported the division.

Calfee, though, said he believes the LeapFrog products developed while he was consulting for the company became good classroom tools.

Professor Eve Clark, a specialist in language acquisition at Stanford University and a researcher at Bing Nursery School, a Stanford laboratory preschool for children ages 2 to 5, said tech toys can be a good thing if used correctly.

Letting a young child watch television for hours on end on a regular basis, Clark said, could be harmful. Research indicates that children under 3 learn best from interacting with people, not from watching programs, she added. Allowing a 4-year-old learning about the alphabet to play an ABC-related computer game for half an hour, though, is probably fine, Clark said.

A 2004 study published in the Official Journal of the American Academy of Pediatrics suggests that children who are exposed to television at a very early age, up to 3 years, have a higher chance of having attention deficit disorder at age seven than those who did not watch television. Television, the study said, portrays rapidly changing images and events that far outpace the rate at which real life unfolds for young children, which can lead to overstimulation.

A 1997 study in Reading Research Quarterly shows that television viewing at a young age reduces reading in later years, as well as self-reported levels of concentration.

Less research has been done on the impact of mobile devices on children, but experts argue that many of the effects, such as overstimulation, are the same.

Today, television and tech devices are a part of almost every child’s life. And that’s not necessarily something to worry about, Clark said. The key, she argues, is using technology as a supplement to and not a substitute for interaction with parents and the other people around them.

“If you’re substituting television for talking to your 3-year-old, that’s not a good thing,” Clark said. “But if your 4-year-old is playing a computer game about the alphabet, there’s probably no harm.”