At 7:45 a.m., everyone in the house on Catamaran Way is wide awake. It’s June 5, primary election day, and Michael Tubbs is ready to face the voters of Stockton’s District 6.

Tubbs mutes his iPhone’s alarm, a wake-up reminder he didn’t need. He folds his hands and squeezes his eyes closed.

“Thank you, God. Keep me humble.”

The whole idea, to some, is audacious: a 21-year-old Stanford University senior trying to unseat an incumbent City Councilman more than twice his age. But to Tubbs, it just feels right.

“The state of the city … the changes that need to be made before 100 youth are murdered,” he says, compelled him to return home and try to “have a seat at the table.” He’s fond of saying, “Whenever you’re in a leadership position, you can’t act like the people you are leading. You have to act older.”

He hops from bed, rushes through a shower, and then pulls on a pair of freshly ironed navy-blue slacks and a linen, short-sleeve dress shirt. Between now and when the polls close at 8 p.m., he wants to knock on more doors, call prospective voters, meet with reporters and make sure his campaign team is in high gear.

Already, though, there’s a glitch. Key members of the team — cousin Shaleeka Powell, campaign manager Nicholas Hatten and intern Chauncy Martin — are running late. Tubbs takes a deep breath and checks Facebook. It’s too early to get flustered, he reminds himself.

In the garage of his mother’s house, Tubbs unfolds two plastic tables and four chairs borrowed from his church, The Congregation of Zion. By 8:40 a.m., Martin arrives and helps set up their supplies, which include 24 water bottles, a handful of pens and packets of voter lists. Hatten joins them a short time later.

Soon Tubbs’s grandmother, whom he calls “NaNa,” delivers two boxes of Krispy Kreme donuts and three boxes of assorted granola bars. Around 9 a.m., high school friend Alexandra Guyton and adviser Ellen Powell, his “Campaign Mother,” arrive as well. “When the press comes, Michael, I want you to be having a serious discussion, so we show that you know what you’re talking about,” says Hatten.

“Yeah, the L.A. Times is coming at 1:00 p.m., and Channel 3 might come. And the Stockton Record might come too,” Tubbs says.

“Where could we go with them? Maybe a school?” Hatten wonders aloud.

A even higher priority right now is to call every name on their list of registered Stockton Democrats in District 6 and urge people to vote. Team members are assigned polling places so they can check who has voted already and cross those names off the call list.

Tubbs is heading off to the San Joaquin County Office of Education.

“I should probably tuck my shirt in, huh?” he says to himself, grabbing a glazed Krispy Kreme.

“All right. Let’s go. Ah, it’s a beautiful day to get elected,” he says, arms stretched wide. He looks up and smiles at the bright blue sky.

Even on the sunniest of days, Stockton is a city beset with problems. Twice named “America’s Most Miserable City” by Forbes Magazine, it is on the verge of bankruptcy. There have been 28 homicides this year, 18 more than this time in 2011. The financial woes have resulted in cuts to police and fire personnel, and city leaders complain about their lack of authority over school system reform, as Stockton is served by parts of four school districts.

Tubbs has lived in District 6 all his life, except for the four years he’s spent at Stanford. The university is 82.4 miles southwest of Stockton, but to Tubbs it’s a different world entirely.

From Stockton to Stanford

Tubbs was raised by three single women: his mother Racole Dixon, grandmother Barbara Nicholson and aunt Tasha Dixon. His mother had him at age 17. His father was in jail for gang- related crimes. Until his mother finished high school, they lived with his grandmother, and then moved around from housing projects to hotel rooms to apartments.

“My mom would come home crying when she didn’t get promotions because she didn’t have a college degree,” he recalls. “She said, ‘You have to promise me that you’ll get your college degree because I don’t want you to be limited.’”

Tubbs will fulfill that promise — and more — on Sunday when he graduates with honors from Stanford. He’ll receive a bachelor’s degree in comparative studies in race and ethnicity and a co-terminal master’s degree in policy, organization and leadership studies from the university’s School of Education.

“I was super busy growing up. Life was very structured. I played club basketball year-round. Wednesday and Sunday, I was in church,” he says. “It was smart because there wasn’t time for me to play in the neighborhood a lot.”

As young as 7, Tubbs was quoting whole chapters of scripture from memory in front of the congregation. He was delivering full sermons by the time he was 12.

At Stockton’s Franklin High School, the 6-foot-1 Tubbs stood out as one of two black males in the International Baccalaureate program and as an outspoken, often quarrelsome student. By the end of senior year, he says, teachers kicked him out of class more than any other student.

“Teachers weren’t used to black students like me. Most of the black students in IB before me were docile, very nice, very quiet,” he says. “None of them were ‘hood or ghetto like me.”

Usually wearing a hoodie and sagging jeans, Tubbs would contest teachers’ comments when he felt they were racist, and he’d argue for better grades when he felt his work deserved better. He now chalks it up to “a fighter mentality, a strong sense of justice.”

At Stanford, Tubbs has experienced the opposite. Being outspoken was no longer a liability.

“My favorite thing about Stanford is the way it can impact so many people,” says Tubbs. “At the core I’ve stayed the same, but… after being at Stanford, there’s really no concept of limits. Why can’t we do it?”

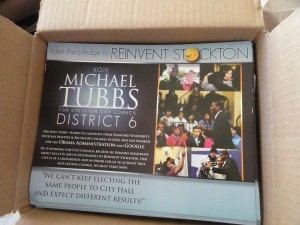

In May of his sophomore year, Stockton friends and relatives began telling him about the murders of young black kids happening frequently in his community. Then his first cousin, Donnell James, was killed. Such violence, which Tubbs calls “an epidemic in which people are dying and they all look like me,” turned his casual interest into a strong desire to run for City Council. His campaign slogan is “Re-invent Stockton.”

“I’m not one of those believers in ‘pull yourself up by your bootstraps’ because I do really see the structural problems in place,” Tubbs says. “That’s why I want to get involved with politics, so I can try to change the structural problems. I’m just not really big on exceptionalism.”

An Underdog Campaign

Stockton’s system for electing council members is unlike that of other cities. A field of candidates is narrowed to two in the primary, based on district-only voting. Then the leading contenders campaign citywide for the general election.

Robert Benedetti, a political science professor at University of Pacific in Stockton, has studied local politics and believes that the system puts a candidate like Tubbs at a disadvantage.

“It means that for a person to win, they not only need to have the name recognition within a district but they have to have that name recognition in the city,” Benedetti says. “When you have a person like Mr. Tubbs, entering as a young person, my guess is his network is focused on the district as opposed to citywide. He’d face a daunting task to introduce himself to the entire city.”

But Hatten, Tubbs’s campaign manager, points to the city’s history as a reason for optimism: More often than not, the winners of the primary go on to take the general election.

Because Tubbs faces only one opponent, Republican Councilman Dale Fritchen, the primary is a trial run for their November showdown. Even outwardly, the contrast is stark — Fritchen, a former social worker, is a 50-year-old Mormon.

While critics of Tubbs think he’s too young and inexperienced, no other Stockton campaign can match his for star power. Oprah Winfrey recently donated $10,000 after speaking with Tubbs at Stanford. “She said, ‘I’ve only given to two campaigns in my life, (Newark Mayor) Corey Booker was my first, Barack Obama was my second, and you are my third,’” Tubbs remembers.

A typical campaign in the city costs $50,000 to $60,000, Hatten says. With Oprah’s donation, Tubbs has raised $30,000 — relying heavily on grassroots campaigning and small donations.

Team Tubbs has been at it since January. On a Saturday in late May, volunteers met at Ernie Shropshire Park in South Stockton for a day of knocking on doors. Hatten advised them to take two steps back from the door after knocking, so as not to surprise the resident as she opens the door.

“Tell them that he interned at the White House and worked with President Obama,” Hatten told them. “Democrats eat that stuff up.”

In a navy dress shirt, pressed black slacks and black Jordan Concords, Tubbs went to the homes of registered Democratic voters in South Stockton, talking to them on their front steps through their gated doors and barking Chihuahuas. In the low-income neighborhoods of Stockton, he listened to complaints about the lack of jobs and safety or the drug-dealer next door.

Starting on 9th Avenue, one of Tubbs’s friends, Ty-Licia Hooker journeyed into a neighborhood in the southernmost part of District 6. She passed by boarded up houses, stepped over empty malt liquor cans and broken brown glass, and walked the few steps to doors guarded by gates, iron bars and dogs, most often Chihuahuas.

“I told him, ‘I risk my life for you everyday Michael,’” she said, laughing. “This house looks like the one where Cain got shot in Menace II Society.”

Counting the Votes

By the time the polls close on primary election night, Tubbs is back in his mother’s house, awaiting the results. He’s joined by aunts, cousins, former teachers and high school classmates, who stand around the high-top kitchen table, squish together on couches, and sit cross-legged on the carpeted floor.

Hatten paces and constantly refreshes his laptop.

“We got numbers!” he yells, and all heads turn.

“Tubbs, 52.5 percent!”

Screams of “Yay” and “Thank you, Jesus” ring around. Tubbs is glued to another laptop, switching between his Facebook page and a live chat on the Stockton Record website. “It’s too early to celebrate,” he says to himself.

By the end of the night, Tubbs had received 54 percent of the primary votes and Fritchen 45 percent. “We still have a lot of work to do until November,” says Tubbs. “And tonight, I gotta finish my thesis.”

Editor’s note: An earlier version of this article incorrectly reported that campaign volunteers were instructed to put material in mailboxes. The article has been modified to correct the record.