Shoes and sandals were scattered across the hallway. Backpacks cluttered the living room. And people, they were all over the place — filling up beds on the second floor, mattresses and couches on the first floor, sleeping bags in the basement. Even outside on the deck overlooking San Francisco Bay, someone had stretched out and gone to sleep. It all looked like one of those college keg parties, where everyone wakes up the next morning with a blurred memory and a great story to tell.

But in the kitchen, instead of finding piles of empty beer bottles, visitors to the Berkeley Hills home would have encountered a silver-haired woman wearing soft pink slippers and an apron, cutting potatoes and carrots. She awakened early that September morning in 1999; she had to in order to get it all done. She was cooking for 21 college students who had come to stay at her house.

“I remember I prepared so much food that morning that I was sure it would be enough for at least a couple of days,” Sigvor Hamre Thornton recalls. “But after the first serving, it was all gone.”

By this time, Thornton was an experienced hand at hosting students who traveled to the Bay Area from Norway in pursuit of higher education. So of course she would make the meals for them and find space for all of them to sleep. “What else was I supposed to do? They needed a place,” she says. “But having 21 sleeping here all at once, that was a bit crazy — even for me.”

It all started in 1952 in the small town of Bergen, Norway. Thornton, then 30, went with her sister to a Cuban music concert in the park and found love. He was a man of letters, the university type. And just a week after saying “I do” down at the courthouse, she followed him across the Atlantic — her first time abroad — and eventually all the way to California, where he accepted a professor’s position at UC Berkeley.

It seemed so foreign at first: the language, the culture, people with fancy university titles and stay-at-home-wives. She was far from friends and family back home. But with her husband teaching Norwegian at Berkeley, there was always some colleague or student with a connection to the Motherland stopping by their house, for a talk or a late supper. She would put on her apron and cook.

It was around the spring of 1968, she recalls, when they decided to take in their first house guest — a Norwegian exchange student who needed a place to stay for a couple of nights. Pretty soon, word spread; there were a couple of other students who needed a place, and then some more.

Word of mouth began its journey, and all of a sudden, the house in the Berkeley Hills had become a natural “pit-stop” for just about any Norwegian student in the Bay Area. Going to UC Berkeley next year, you say? Oh, you’ll have to stay at Sigvor’s. Headed for studies at Stanford? Going to San Francisco? You simply must give this Sigvor lady a call.

She became an institution. And they gave her a name.

Mother Norway.

‘I like most people’

Some 40 years after welcoming her first guest, Thornton has lost count of how many people have crossed her doorstep. But surely the number is in the hundreds, maybe thousands.

In October, she will turn 92. She lives alone in the same two-story house, which is getting increasingly hard to maintain. Her upper back curves toward the ground, her ulcer keeps acting up. Still, she continues to invite students in.

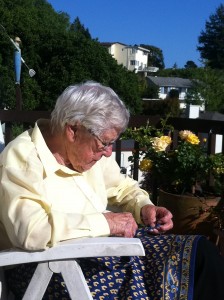

Proof is in the stack of leather-covered guest books that she keeps on the coffee table in the living room, next to the knitting bag and the bowl of M&Ms. Three of them are filled from cover to cover, now the fourth is starting to fill up. Thornton rests the guest books in her lap and lets her fingertip shiver across the pages. Distant memories come to life.

The first entry was recorded on Good Friday, 1968. “Oh yes, that guy, I remember him. He was a real charmer,” she recalls. Then there’s the student who would later write the name of “Mrs. Thornton” in the acknowledgements of his books and academic work. “Really, did he do that?” she says and smiles timidly.

Also in the book are signatures of that happy-go-lucky group of students she remembers for their jokes and pranks. Many went on to become famous lawyers or professors in Norway. And that guy, “didn’t he become Norway’s first secretary of oil and energy?” she says, pointing to yet another name.

And then, of course, there was her brush with royalty.

She remembers it well. It was a chilly October Tuesday last year. Thornton had put on her silver earrings and a dark pink blouse for the occasion and was standing with pride next to the Norwegian diplomatic representative based in San Francisco. Along with the priest of the Norwegian Seamen’s Church, they had lined up along Hyde Street, waiting to welcome their country’s Crown Prince, Haakon Magnus, who was on an official visit to the Bay Area.

When the prince arrived, he shook hands, smiled politely, and nodded his good mornings and thank yous as he worked his way down the line. Finally he stood in front of Thornton, and a large smile drew over the 37-year-old prince’s face. “Sigvor! It’s you!” He folded his hands around hers and leaned down closer toward her wrinkled smile. “How great to see you! How are you? It’s been far too long…”

Of course she knew the Crown Prince on a first-name basis. He had, like so many others, come to her house when he was a UC Berkeley student in the late 1990s. The first time he visited, Thornton remembers, was to attend a party she had thrown together in her garden for some 50 or 60 students. The prince appeared, with a full set of bodyguards.

The second time he came, he told his guards they could stay in the car outside. The third time, he told them that they could just go home, that he would be fine. “I think he really enjoyed himself,” Thornton recalls. “A mediocre student they tell me, but he was just the sweetest guy.”

With the garden parties, the sleep-overs and the seemingly constant open door, more and more people found their way to her house. One time, a Norwegian university principal who was visiting the area gave Thornton a call and asked if he could come over for dinner, and could he bring a couple of friends and business connections as well? “Probably around 10 people,” he said. Sure, no problem, she replied. Then he called again the next day. “Actually, we’ll be closer to fifteen.”

That’s fine, Thornton said. On the third day, he called again. “Actually, it turns out that a couple of more people have heard about this get-together, and they too would like to come. So it won’t be fifteen. I think we’ll be closer to 44.”

It never occurred to her to say no. And though she’s still hesitant to admit that things ever got out of control, or that it was all becoming a bit too much for her to handle, the turning point came in 1999, when the 21 students came to stay.

Up until then, everything had always been free of charge — the beds, the long showers, the meals. But now, an aging widow, and after a week by the kitchen stove (“I baked bread for them every day,” she remembers, “sometimes twice a day”), she decided she would have to start setting boundaries. No more 20-something crowds staying at the same time. No smokers. And, finally, no more “free lunches.” She would have to start asking for help to cover her expenses.

But it was never about the money, Thornton assures. “You can’t do this kind of thing unless you’re a people person,” she says. “Me, I like people. Or at least, I like most people.”

Harboring so many youngsters over the years, she has had her share of bad encounters. Like the heavy drinker, she remembers, who just sat on her couch all day and ended up stealing beer from her refrigerator. Or the girl who refused to share a room with anybody, even if the house was full of people. The same girl also refused to clean the table or help out with the dishes, like all the other guests did. It got so frustrating that one day the other students collectively decided to block the kitchen door and refused to let her leave the room before she too had gotten her hands dirty and done her share of the dishes.

“I don’t know if she learned a lesson or not. She was just terribly spoiled,” Thornton says.

And there have been the occasional no-shows. One group — they were maybe 10 or 12 students — emailed her and told her they would like to come stay for a couple of nights. You are all very welcome, she responded. But when the day of their arrival came, no one showed up. Thornton, like a worried parent, sat up until 1 in the morning, waiting and looking for them.

But her face lights up when the dearest of encounters come to mind. Two young students, who coincidentally stayed under her roof at the same time, fell so desperately in love that they lost track of everything but each other and could just never get around to their classes in time. And one boy – he was so painfully shy that he couldn’t bare to look anyone in the eye, let alone engage in any conversation. But all of a sudden, he blossomed, he opened up. Actually, quite a few of them did.

“Probably because I was so old and they didn’t have any close family nearby, they felt that they could tell me things,” Thornton recalls. “So they would come sit on my deck and tell me what was going on in their lives: the latest drama, who they were in love with, who had just broken up — you know, the important stuff.”

Sense of security

Years after those quiet conversations on the deck, the same students will write to her and invite her to their weddings or to their babies’ christenings. Some of them also keep coming back to visit her. One, who eventually settled down in the Bay Area, even has his own key. He’ll stop by on a regular basis, just to chat, freshen up her flowers, or simply check that the old lady is okay. “He’s almost like a son to me,” Thornton says.

Having the extra people around also gives her a sense of security. It’s not easy growing old, not easy living alone. The once light-footed Thornton, who used to run up and down the stairs to the garden to serve her guests, has gradually come to terms with the fact that her feet are not as quick as they used to be. And though she still takes in student guests, and she still cooks all their meals, she now pushes a little stool in front of the kitchen stove, so she can rest her back while tending to the casseroles.

Not long ago, a couple of burglars smashed a window and broke into her house. It was only thanks to a student guest staying in the basement that they discovered the two intruders and chased them out the door. For decades past, students have depended on and needed Mrs. Thornton. Now, she may need them just as much.

Sure, she has family of her own, six step children — four from her first husband, and two from the man she married after he passed away. Mother Norway never gave birth herself. “I accepted it,” she says about her sacrifice. “I guess I was afraid that if I insisted on having a baby of my own, I wouldn’t be able to be fair to the other kids, and to love them all equally. And that was important to me. So that was it – I wouldn’t have kids of my own.”

On a recent Tuesday, the 91-year old hosted yet another group of young people. Some were living in her basement, the rest came from around the Bay Area. When they arrived, she welcomed them with hugs and a big smile. She served homemade meatballs with cranberries and pea stew.

And soon enough, once again, there was laughter and stories.

After dinner, when it came time for some of the guests to leave, attention turned to the leather-covered books on Thornton’s coffee table. The guests would have to write a little message. They turned the pages and found a blank spot, next to the seemingly endless row of testimonials left by others before them.

Stories of gratitude: “Thanks for saving me at the airport, Sigvor. You’re an angel. Martin.”

Stories of giving back: “I’m leaving you with a tape of some of my music. Take care. Chris.”

Stories of youthful optimism and adventure: ”Sigvor, come join us for the party! Broderick Avenue. Best, Lene.”

Stories of generations passed: “My father sends his regards. He also came to stay here many years ago. Fredrik.”

And finally, the heartfelt goodbyes: “This was just like coming home to my Mother. Thank you, Sigvor.”