An organization devoted to ridding the world of AIDS is asking a company developing cutting-edge HIV treatment and prevention drugs to slow down.

The AIDS Healthcare Foundation says Gilead Sciences has rushed testing of a controversial drug that would allow people at risk of getting HIV/AIDS to avoid contracting the infection by taking a pill before engaging in risky sexual behavior.

Now, the foundation is protesting Gilead’s application to the FDA for approval of the drug Truvada, a pre-exposure prophylaxis, or preventative measure. It argues that using the drug might lead people who assume they are protected by it to engage in unsafe sex. The foundation says Gilead should be focused on bringing affordable HIV treatments to infected people around the world, not on marketing a preventative drug.

But the Foster City pharmaceutical company says it simply wants to bring the most innovative drugs to patients.

Whitney Engeran, senior director of public health at the AIDS Healthcare Foundation, argues that Gilead has rushed testing of Truvada in an effort to dramatically expand the company’s market.

“If you expect to see 2,000 new cases of HIV this year in Los Angeles County, and then you go out with a pre-exposure prophylaxis, by identifying people with certain characteristics, you’re talking about hundreds of thousands of people,” Engeran said. “So, from Gilead’s point of view, it’s great.”

Kacy Hutchison, director of government relations for Gilead, takes a different stance.

“Our efforts are founded on the mission of meeting unmet medical needs,” she said.

Hutchison knows well the intense behind-the-scenes lobbying that surrounds drug approval. With a political science degree from the University of California at Berkeley and a law degree from American University in Washington, D.C., Hutchison joined Gilead five years ago after serving as deputy legislative affairs secretary for former Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger.

She now spends the bulk of her time encouraging states to reduce barriers to HIV testing and working with advocacy groups, like the California Hospital Association, to find new ways to offer testing to people who might not otherwise get it.

The AIDS Healthcare Foundation supports Gilead’s efforts to streamline testing, and even worked with the company to do so. New York City now must offer the test, and the Department of Motor Vehicles in Washington, D.C., offers it in an attempt to reach people who might not ordinarily go to a clinic to be tested. But, Engeran argues, it all comes down to pricing, and Gilead Sciences needs to budge.

“We’re in sympatico with them on a lot of their interests and making testing easier and faster is a good thing,” he said. “I applaud them for that, but at the end of the day, Gilead has to be thinking about the price of its share and the market, and about growth as a company to be viable.”

According to Hutchison, the evolution of Gilead hinges on the ability to bring new drugs to market – an expensive undertaking. The average cost of bringing a new drug to market, she says, is between $800 million and $1 billion. Even so, she argues, Gilead has issued generic licenses that have reduced costs and helped millions of people access lifesaving HIV/AIDS drugs, all while working to develop and improve treatment and prevention.

“When we began, people were taking 20 pills per day. Now we’re down to one,” she said. “We’re never going to satisfy 100 percent of the people.”

Brook Baker, a law professor at Northeastern University and a health-policy analyst with the Health Global Access Project, an AIDS activism organization, says Gilead could do a lot more to bring drugs to different people across the world.

“They try to get stronger protections for their patents domestically by making minor tweaks to the drugs,” he said, “and they get patent extensions that have global implications by preventing the production of cheaper generics in other countries.”

The AIDS Healthcare Foundation agrees, saying that the faltering economy has made it especially difficult for people to access drugs, but that Gilead has done little to help.

“Recently, they did lower prices and agreed to give more rebates so people can be taken off waiting lists,” Engeran acknowledged. But he also expressed concern about Gilead pushing a preventative drug just to expand its business.

Baker also voiced reservations about the implications of approving a preventative drug.

“Patients who don’t know their status and take a pre-exposure prophylaxis will develop resistance if they’re positive, and pass on a resistant strain to their partners, so there are definite treatment concerns,” he said.

However, Jim Rooney, a physician and vice president of medical affairs for Gilead, wrote in an email that no cases of a person becoming infected, developing resistance, and then passing that resistance on to a partner have occurred in a pre-exposure prophylaxis trial.

“The resistance mutations that have been reported are consistent with those seen in patients receiving HIV treatment,” Rooney wrote. “In addition, there are numerous antiviral treatment options for effectively treating and suppressing this subset of patients.”

He also stressed the importance of monitoring and testing the HIV status of patients both before and during the use of Truvada as a preventative measure.

The AIDS Healthcare Foundation wants the FDA to release its correspondence with Gilead regarding Truvada as a form of HIV prevention. The organization held a protest at FDA headquarters in Washington, D.C., last month to pressure officials to release the correspondence, but so far the FDA has refused. The agency declined to comment about their correspondence with Gilead.

“The protest went well,” Engeran said. “With the FDA, we’re very concerned they’re rushing it. We just need the administration to know that we’re watching them, and that we think they’re moving too fast.”

He says the drug should be approached cautiously.

“Gilead is rushing because they have to keep their stock price going up,” he charged.

Gilead is not the only player in the debate using lobbyists to gain support for their positions. The AIDS Healthcare Foundation employs several lobbying firms in Sacramento and Washington, D.C.. It recently gave a van to an organization in Los Angeles that works with African-American men, allowing the group to go out into the community to meet and test people for HIV.

“We do most of the work ourselves,” Engeran said. “In terms of paying other agencies, we do try to give grants to help people do work on the ground.”

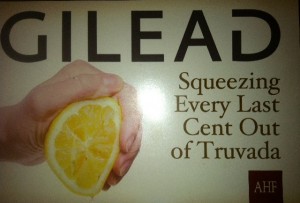

In addition to public protests like the one at the FDA, the organization also sent postcards to residents in Foster City, where Gilead is located, to draw attention to the conflict.

“Gilead is trying to ram Truvada for HIV prevention through the FDA despite serious concerns about its safety and effectiveness,” the postcard says. It features a picture of a hand squeezing a lemon and the words, “Gilead: Squeezing Every Last Cent Out of Truvada.”

Hutchison, by contrast, is an in-house lobbyist for Gilead, working for the company full time on more traditional lobbying campaigns. Gilead is so large that lobbying duties are divided, and she has little to do with lobbying the FDA for patent approval. She focuses on lobbying legislators and their staffs about reducing testing barriers.

Both sides agree that the current economy has made the job of lobbying officials to devote increasingly limited funding to their causes more difficult.,

“There’s no money left,” Hutchison said. “You used to be able to say, ‘You can’t touch K-12 education funding, or HIV funding,’ but there’s nothing left.”