“Ready Pete?”

“Yeah” Lavorato replied. Jim Harbaugh swung open the door. His Stanford football coaching staff, offense and defense, streamed in, their notepads ready. A cold sweat enveloped Matt Moran, Lavorato’s assistant coach. Lavorato’s eyes widened. He had not envisioned this. He expected a casual conversation with Harbaugh. Instead, 20 coaches sat in a Stanford football office, staring at him.

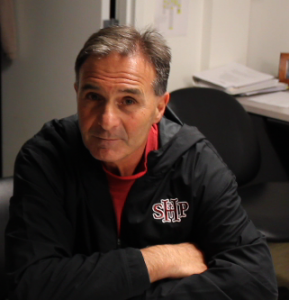

To Lavorato, the office suddenly felt like an oven. It had become Stanford’s newest classroom, and the coaches expected to learn from their professor. The curriculum that day was the “fly” offense, and the professor, Sacred Heart Prep coach Pete Lavorato.

The meeting lasted half an hour. Lavorato drew the plays on the white board as the coaches listened. He explained the Xs and Os, and also the concept behind the offense. In the “fly” offense, the receiver races towards the backfield, accelerating to full speed by the time the quarterback hands him the ball. The defense is standing still. It becomes like a drag race: one car starts at 60 miles per hour and the other in park.

Lavorato’s face lights up when he remembers that meeting. How strange it felt teaching college coaches his high school offense. But his face glows when he recalls seeing Stanford players run the fly. Harbaugh used the play sparingly, but with great success. Most notably, Harbaugh used speedster Chris Owusu to sweep around the defense for multiple first downs during the 2009 season. (Story continues below.)

[youtube]-aCXNJbENfI[/youtube]

In summer 2011, the San Francisco 49ers named Harbaugh their head coach. He moved up the Peninsula from Stanford to Candlestick Park, and brought Lavorato’s offense along.

Last October, Lavorato sat in a Jake’s Pizza watching Harbaugh’s 49ers on TV. He came by himself. He wanted to be alone for the game, just pizza and football.

San Francisco stepped to the line, quarterback Alex Smith lifted a leg and wide receiver Tedd Ginn Jr. jogged towards the backfield, accelerating. The center snapped the ball, Smith swiveled and held out the ball as Ginn streaked by and snatched it. Ginn flew around the edge, legs churning, defenders falling behind. The defense eventually forced Ginn out of bounds, but not before he gained 16 yards and a first down.

Lavorato stared at the screen, pizza forgotten. That was his play. The one he taught Harbaugh two years earlier. San Francisco ran it faster, called it differently, and played in front of 80,000 fans, but the sweep executed the same. The bartender saw his reaction and strolled over and said, “Yeah, that’s the fly sweep. Harbaugh got that from some high school coach up in Atherton.”

The guru of the fly offense

Suddenly, Lavorato’s name began bouncing around the Internet like sneakers in a clothes dryer. Harbaugh proclaimed him “guru of the fly offense.” Strange numbers appeared on Lavorato’s caller-ID, reporters and coaches from around the country looking for “the guru.”

Lavorato seems immune to the burst of publicity. “I’m just a decent high school coach, ya know,” Lavorato said. His wife, Nancy, attributes his being unfazed by the attention to his Canadian roots. “They’re just wired different,” she said. “I mean, he’s wired all right, just differently.”

Or maybe, the spotlight didn’t startle Lavorato because this wasn’t his first encounter with it.

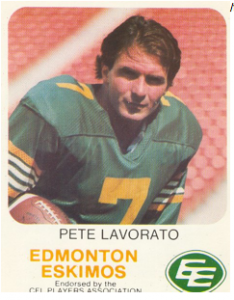

Lavorato grew up in Edmonton, where he played just one year of prep football at Austin O’Brien Catholic. Ray Jauch, then head coach of the Canadian Football League’s Edmonton Eskimos, noticed Lavorato and used his connections to get Lavorato on the team at Utah State University.

Lavorato’s first varsity start came in the second game of his sophomore season, against the No. 4 Oklahoma Sooners in Norman, OK.

“We get there,” recalls Lavorato, “and there’s more people just standing there, waiting three hours before the game than I’d ever seen before in my life. I said to my buddy ‘What are they doing here?’ He says, ‘They just wanna see us get off the bus.’”

The Sooners crushed Utah State 49-0. Lavorato clearly remembers Oklahoma’s wishbone offense: “I made 20 unassisted tackles, but never once did the guy have the ball.”

More than 62,000 fans packed Memorial Stadium for that game. It was Lavorato’s first encounter with the national stage, but not his last. After graduating, Lavorato signed a contract with Jauch and his hometown Edmonton Eskimos.

Hugh Campbell succeeded Jauch in 1977, bringing with him an undrafted quarterback from Washington named Warren Moon. Lavorato won five Grey Cups (Canadian Super Bowls) with the Eskimos.

“He was a ferocious tackler,” Campbell recalls. “Very, very competitive. A high quality guy with concern for his teammates.” The league voted Lavorato to its All-Star team in 1977, and the city adored the hometown hero.

When injuries forced Lavorato to give up football in 1982, Nancy suggested coaching, but the job appealed little to him.

“When I was playing with the Eskimos,” Lavorato recalled, “people would call me to come out and be a guest coach for high school or Pop Warner. I did it once at my alma mater and hated it.”

However, Lavorato had a young family to support, so he agreed to give coaching a try. He held several coaching jobs in the 90’s, moving between California and Edmonton.

Sacred Heart hired Lavorato in 2003. When he arrived the school’s football stadium consisted of a rusty set of bleachers, and a dingy basement served as locker room. The varsity listed 20 boys on its roster. Some days the team couldn’t rustle up enough players to practice. Lavorato took it all in and declared, “Let’s build something.”

Since 2003, Lavorato has done just that. Today, a beautiful stadium adorns Sacred Heart’s campus with a field-turf surface and an immaculate locker room. Over the past eight seasons, the Gators’ record is 64-27, including a section championship. Lavorato attributes much of that success to the fly, though, he does not claim to be the originator. Lavorato says that honor goes to another Bay Area high school coach, Palma’s Norm Costa.

Several years ago Palma scorched Lavorato’s defense, and after the game Lavorato asked Costa about the Palma offense. Costa sent Lavorato his playbook, and since then, Sacred Heart has been using the fly to become a perennial playoff team.

But more than wins, Lavorato has built a community. The program has grown to more than 100 players. Lavorato also introduced a new word into SHP’s football vocabulary: love.

Chris Gaertner, former SHP player now at Stanford recalls, “After every practice he would say, ‘What is my job?’ and the players would answer ‘To love us.’ Then he would say ‘What is your job?’ to which we would respond ‘To love each other.’”

Lavorato is a man of faith. At season’s end he presents each senior with a Bible, personalizing a message in every one.

In November, the 49ers named him Bay Area High School Coach of the Week and presented him a football autographed by Harbaugh. Lavorato donated the signed football to an auction benefiting breast cancer.

Sacred Heart Athletic director Frank Rodriguez says of Lavorato, “He walks the walk.” That walk led him to Utah State and the CFL. Later, it led to Sacred Heart, and briefly, to an office at Stanford, and into the spotlight.