Where some might gaze out at the San Francisco Bay glittering under a gentle sun and see nature in a state of serenity, Ethan Estess can’t help but see a paradise that has been ravaged by human pollution, especially disposable plastics.

The explosion of single-use plastic products, like utensils, cups, packaging, and shopping bags, over the last several decades’ has transformed Estess’s ocean haven into somewhat of a dump. Instead of standing idly by, this master’s student in Stanford’s Earth Systems program set off to raise awareness for this problem through art.

Sixty to 80 percent of marine debris comes from land-based sources, with as much as 80 percent of that being plastic. But rather than overwhelm people with these abstract figures, Estess gives these numbers meaning by creating masterpieces from trash. Art, he believes, offers a way to express the environmental issue of ocean pollution more effectively by targeting people’s emotions.

“Most of the communication that’s going on through media are outrageous statistics that are completely out of context,” Estess said. “When we’re bombarded with that kind of information, I think it just kind of bounces off of us, and it isn’t really meaningful because that’s just not how we make decisions. We use emotion whenever we make decisions.”

On a recent winter day, Estess positioned himself into the frame, skipping over the rocks to beat the self-timer ticking on his camera, and tilted his head back to drink from a disposable coffee cup, with the Bay as his backdrop. But trailing behind him are 8,000 plastic cup lids flowing like tentacles from his backpack, representing the vast amount of waste that people thoughtlessly create as they go about their lives, sipping from their routine cups of coffee to go.

This picture was the cover image publicizing his January art exhibition called Stories from the Changing Tide. His work was sponsored through Recology San Francisco’s Artist in Residence Program, which gives artists access to materials headed for the landfill or recycling facility that can instead be used for their craft.

Scientists are noticing that our oceans are increasingly turning into plastic soups as more single-use plastic products are swept off streets into storm drains and picked up from overflowing landfills by the wind. Once plastics find their way to the sea, the sun’s UV rays decompose them very quickly to particles smaller than five millimeters.

At this size, the particles are likely to be ingested by birds, fish and marine mammals that eventually die from their inability to process this plastic, or even from poisoning. Decomposed plastic leaches toxic chemicals that are known to be endocrine disrupting and carcinogenic. What is especially alarming, says Communications Director Stiv Wilson of the environmental nonprofit 5 Gyres, is how these poisons are moving up through the food chain, at the top of which are humans.

“When you’re eating sushi,” Wilson says, “you’re eating plastic.”

The declining health of our oceans from plastic pollution, and perhaps even the decline in human health, is the result of people’s “addiction to convenience,” Estess says.

Both Estess and Wilson believe that legislation aiming to reduce people’s consumption of plastic is important to combating further environmental destruction.

“There’s no evidence at all, unequivocally, that voluntary reductions in plastic bag usage work,” says Wilson. “The only things that have worked are bans or fees associated with the consumption of plastic.”

San Francisco was the first city in the nation to eliminate plastic shopping bags from large supermarkets and chain pharmacies, in 2007. Since then, six other counties and 37 cities in California alone have followed suit, adopting similar bans.

“This legislation is a catalyst of change,” Estess said, creating a culture of environmental stewardship that will make Americans think twice before mindlessly choosing convenience. Citing findings from Ireland that saw a 90 percent drop in plastic bag usage after imposing its ban, Estess is convinced that these laws “absolutely reduce the number [of plastic bags] entering the environment no doubt. It’s a win for the coastal zone.”

Wilson believes the bans’ success is from making people realize that as a society, “we can eliminate these because they’re unnecessary, and why are we polluting the environment with unnecessary things?”

Yet, others like Stephen Joseph, counsel for the Save the Plastic Bag Coalition (SPBC), feel that single-use, disposable items are integral elements in our consumer society.

“Zero waste equals zero economy,” Joseph says. “Our livelihoods are built on waste.”

Not surprisingly, the Save the Plastic Bag Coalition is behind litigation that could stall cities’ efforts to remove plastic bags from this cycle of waste.

Most recently, the group has filed suits against San Francisco and the city of Carpenteria, arguing that the cities are in violation of the California Retail Food Code for trying to restrict plastic bags at restaurants. San Francisco, it adds, also violated the California Environmental Quality Review act by not submitting an Environmental Impact Report before it passed the broader ban on plastic bags that would now extend to all retailers, along with a 10-cent fee on paper bags.

Trapped in constant political vitriol and litigation delays, legislation offers a partial answer to reducing our impact on the environment. But rising above this conflict, Deborah Munk believes Estess’s art informs and inspires others to care about marine pollution. Recology San Francisco’s program director was blown away by his exhibition, which she says was “the most crowded show ever,” attracting approximately 700 visitors.

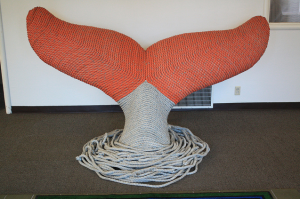

Munk noted how captivated visitors were by the powerful statements his art makes about marine destruction. One piece in particular, a giant whale fin coiled in rope entitled, Last Dive at the Farallones: 100,000 marine mammals killed per year, she believed was “very impactful” among the viewers.

“The kids, the adults, it was the first thing they saw and it just got so many exclamation marks,” Munk recalled. “It was the most well received piece of the evening.” Estess’s art has continued turning heads as it has been featured at San Francisco’s 9th Annual Ocean Film Festival in March.

Whatever comes next for Estess, one can be sure that the thoughtfulness and eco-consciousness that transcends his art will continue to color his everyday decisions.

“Could I have it in a mug, please,” Estess says to the Coffee House cashier on campus, ahead of a recent interview with a reporter. Suddenly, there’s a pained look on his face as realizes his wooden stirrer must be thrown away after only a few quick swirls.

“I hate single-use things,” Estess says, gritting through his teeth, hesitating as he holds the stirrer above a black hole into garbage oblivion. But at the last moment he lets go a sigh of relief as he spots a compost bin, and drops the stirrer in with a satisfied smile.

For Estess, this broader issue of saving our oceans won’t be solved simply by focusing our plastic footprints, but will take broader environmental awareness that informs all of our actions.

“I’m trying to use the science as a framework, and then connect that with making somebody feel a certain way and maybe that will change the way they behave,” Estess explains. “And there’s a big jump there, does that actually translate into action? All it takes, though, is getting that concept into somebody’s conscience.”