If you had a 50-50 chance of inheriting a genetic disease, would you get tested to know? Or would you wait for fate to reveal itself years later?

Would your decision change if you knew the disease slowly takes away the ability to walk, talk, and even think?

What if there was no cure?

Kristen Powers let those questions hang in the air as she spoke to a dozen middle and high school students on a sunny spring afternoon. The slender, 19-year-old Stanford University freshman was taking part in a program that allows undergraduates to teach classes on topics of their choosing. Today’s class — “To Test or Not to Test? The Ethics Behind Genetically Inherited Disease” — would cover a subject that Kristen knows far too much about.

“How many of you know what Huntington’s Disease is?” she asked, only to find herself met with a few raised hands amongst mostly blank faces.

Kristen smiled. The response wasn’t surprising considering that the disease affects men and women at a rate of 1 in 10,000 people in Western countries. She pointed at one of the few raised hands. “It’s a disease where your brain cells die, and you start to lose control of your body, and then you die,” said the ninth-grade girl who had been called upon. Kristen pushed a lock of her dirty-blonde hair behind one ear and nodded. After all, the girl was more or less correct.

Huntington’s Disease (HD) is a neurodegenerative genetic disorder that, as it progresses, affects the ability to think, move and feel. Most patients begin to show symptoms between the ages of 30 and 50 and typically succumb to the disease 10 to 25 years after the first symptoms appear.

A person with HD has a 50-50 chance of passing the disease on to every individual child that he or she has, making this a devastating family disease.

“My mum passed away from Huntington’s in 2011, when she was 45,” Kristen continued, quickly capturing the attention of her audience. The implications of Kristen’s statement were clear to all in the room.

“I like to joke that I’m information-needy, so when I turned 18, I decided to get tested to see if I had HD, too.”

Genetic testing for Huntington’s involves DNA sequencing to see how many repeats of a certain codon exist in a person’s genetic code. A normally functioning individual has between 10 and 35 of the C-A-G codon, while a person with Huntington’s has 40 or more. Researchers are still not sure what happens to individuals with 36 to 39 repeats, as studies have shown a variety of results.

Kristen’s mom, who inherited the disease from a biological father that she never knew, had 47 C-A-G repeats.

“I watched my mom go through a lot during her last few years,” Kristen told her now-attentive audience. “I knew I had to get tested because, if I had HD, I’d have to adjust my timeline for my life. I’ve always wanted to travel, and I knew that that was something I’d have to do earlier if I tested positive.”

The girl who had defined HD was now on the edge of her seat, eyes wide open. She looked terrified that her flippant response was predictive of Kristen’s fate.

“So last year I got tested, and I’m happy to say that I tested negative.”

And just like that, the tension in the room lifted.

Life after Testing

Kristen’s negative test result means she will never develop the disease that claimed her mother’s life, and she has no chance of passing it on if she has children.

“It’s actually really weird knowing that I’m never going to get Huntington’s,” Kristen said in a recent interview, “because up until I tested I always assumed that I would die of HD, and it was scary but at least that was certain. As soon as I tested negative I feel like my whole life changed because, all of a sudden, I had no idea what I was going to die of anymore.”

She laughed and continued, “I remember being really surprised and thinking ‘Wow, this is what normal people feel like!’”

Still, Huntington’s Disease remains a prominent part of Kristen’s life. She has devoted herself to raising awareness of the disease and doing what she can to help find a cure.

Her strategy for doing this involves working as a student researcher in the Huntington’s Outreach Project for Education at Stanford (HOPES), volunteering as an advocate for the Huntington’s Disease Society of America and, most importantly, making a documentary about her genetic testing process.

The documentary, which she has entitled “Twitch” after the muscle spasms that are symptomatic of HD, follows Kristen through the emotional and medical journey that she embarked upon in order to discover whether she had inherited the disease.

“Growing up, I always wanted to make a documentary because I thought it was a really cool way to raise awareness. I grew up on ‘An Inconvenient Truth’ and ‘Food Inc.’ and those were really inspiring to me,” Kristen said. “In the summer of 2011, I was nearing my 18th birthday and starting to think about getting tested. I started mentioning the idea to a few others and through the environmental work I did in high school, I met some people who helped me realize that making this [documentary] was very feasible.”

Connections from her previous nonprofit work and a skillful use of social media have helped Kristen raise nearly $30,000 for “Twitch.” The funds have gone towards helping her hire a film crew and editor, whom she works with in between attending classes and hanging out with her Stanford roommates.

“School comes first,” she said with a smile. “I’m still trying to pick a major and figure all of that out, very normal college kid stuff.”

Picking up the Camera

That normal college stuff means picking a new roommate for her sophomore year (her original roommate plans to move into a sorority house), scoping out a summer vacation spot (she’s settled on Florida for now), and mediating conflicts on her dorm hallway (where she’s known for her laid-back personality and calming voice).

It’s a refreshing and welcome change for someone whose childhood was consumed by much more serious things.

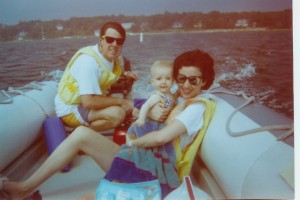

Kristen was 7, living in Massachusetts, when her parents divorced and she moved in with her mother. It wasn’t long before she started to notice symptoms of her mother’s disease. “I remember her walking around like she was drunk, but that was before we knew what was wrong with her. In retrospect, she showed signs [of Huntington’s] as early as when I was 2.”

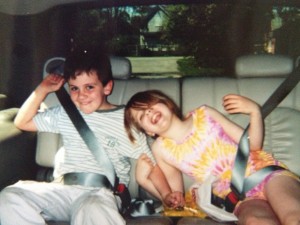

Her mother, Nicola Powers, wasn’t diagnosed with Huntington’s until two years later. Within months, her mother’s disease progressing at an alarming rate, Kristen and her younger brother had no choice but to move in with their dad in Boston.

Nicola moved in with her parents, who took on the role of primary caretakers, when Kristen was 11, and then was placed in a nursing home in January 2006.

It was during this time that Kristen first brought out her video camera.

“I used to sneak the camera into the nursing home and secretly videotape her,” Kristen said. “My grandma wasn’t a fan of it.”

Though Kristen didn’t decide to make a documentary until 2011, she knew she’d forever regret not having video footage to remember her mom by. “It was incredibly weird to film,” she recalled. “I wasn’t sure what my mum was thinking of me secretly recording her, she couldn’t speak to tell me if it was weird. Also, it felt like everyone in the nursing home was staring at me.”

“I didn’t understand why it was so strange to want to remember who my mum was, even if she wasn’t in her prime,” Kristen added.

Now, however, the footage serves as more than just mere remembrance, as much of it has ended up in the documentary. She believes the film, when completed, will help explain and show the effects of Huntington’s Disease.

“I’m incredibly glad I did it,” Kristen said. “Families with terminally ill members should not be afraid to record memories with their loved ones.”

Above all, the experience has taught Kristen the importance of documenting the lives of loved ones, regardless of whether there’s a compelling reason to or not. “If I could go back in time, I would make sure that we got more photos and videos of my mum in all stages of her life. That’s what I’m trying to do with the family I have now.”

All in the Family

“I want to make this the last generation with Huntington’s Disease,” Kristen declares in the trailer for her documentary.

While her statement may seem bold, it’s unsurprising that Kristen has continued to dedicate so much of her life to Huntington’s. Her 17-year-old brother, Nate, is still at-risk.

Nate, a junior in high school, lives at home with his dad and adoptive mom in Chapel Hill, North Carolina. He becomes eligible for genetic testing in March.

“It’s really hard sometimes because we have to keep reminding ourselves and other people that, just because I tested negative, that doesn’t mean Nate is going to test positive,” Kristen said. “That’s not how it works. We could both not have the disease.”

During a recent visit to Stanford, Nate said in an interview: “It’s really easy to hear 50-50 chance and think, ‘Oh well … Kristen doesn’t have it, then that means I do because I’m the other 50 percent. Having Kristen go through testing first was really helpful because I had doctors and my parents and people constantly reminding me that that wasn’t true.”

Despite initial hesitations, Nate is now strongly leaning towards getting tested next year before he leaves for college. He said the test results would influence how he approaches certain aspects of his life, such as future relationships.

“I wouldn’t have kids if I tested positive,” he said. “I just know that’s something I wouldn’t want to do because then I might pass [the gene] on.”

Kristen has made it a personal goal to be as supportive as possible of Nate.

“It’s entirely up to him whether he wants to get tested,” she said. “For me, I knew it was the right thing to do. For him, it may or may not be, but he’s my little brother and I’m going to be there for him.”

Until then, Kristen plans on working on finishing her documentary and keeping herself busy with school and her other extracurriculars, like learning how to hip-hop dance.

“I still remember the genetic counselor coming in, and sitting down and saying ‘We have good news for you today,’” she said, smiling. “I heard that and my dad started crying and I couldn’t really process anything. It was just an ‘Oh my god!” sort of moment, and, for now, I’m just going to hope that my family has that moment again.”

Editor’s note: Ravali Reddy, like Kristen Powers, is a student worker in the Huntington’s Outreach Project for Education at Stanford (HOPES).