QUESTION: When disposing of food waste, I often compost. But some food wastes are not supposed to go in the compost pile. Is it more environmentally sound to scrape your plate into the trash or send it down the kitchen disposal? Asked by Lauren Woodard, Houston, Texas

ANSWER: Food waste is more than a pet peeve to me. Leftovers that have gone bad in the refrigerator or a slurry of dinner scraps not worth saving bother me so much that I risk my personal health to consume the world’s leftovers. At dinner parties I often finish strangers’ meals to keep them from going into the garbage. What is a better approach?

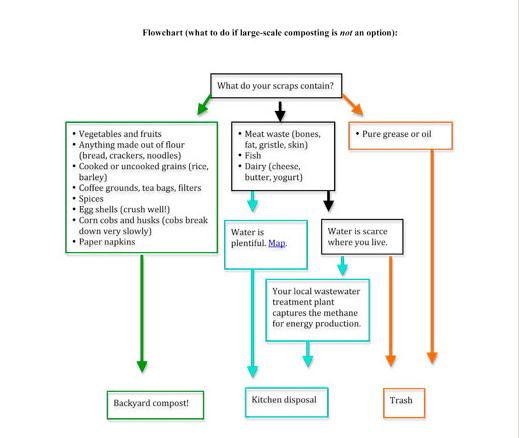

First, you’re right: composting is the preferred option. It’s also underrated, and underused. If the 21.5 million tons of food waste generated annually in the United States were composted instead of being sent to landfills, the cut in greenhouse gas emissions alone would be like taking over two million cars off the road—and that is hardly compost’s only benefit. More food residues and paper products are fit for compost than commonly thought, too. The important distinction is between the somewhat limited backyard compost pile and the much more inclusive large-scale municipal or commercial composting operation. I’ve created the flowchart here to help you decide the best fate for your food and paper waste.

Oils, meat residues, dairy, and human waste are the big No-No’s of backyard composting. Under the right conditions, compost piles generate enough heat to kill any potential pathogens—in a used tissue, for example. However, backyard composts often do not reach those optimal temperatures, and meat and other animal waste can attract critters if food takes too long to decompose.

Large-scale composting facilities are not widespread, but they are growing in number. San Francisco already offers curbside composting pickup, and voters in Palo Alto, Calif., recently approved a new anaerobic compost digester on ten acres of former landfill. Peter Drekmeier, a former Palo Alto mayor, calls this advanced composter, which will turn food waste, yard waste, and human waste into biogas and compost, “a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity.” Land is available to process three waste streams, produce renewable energy and excellent fertilizer, and reduce greenhouse gas emissions. “Any place that has [a] sewage treatment plant should also process food waste,” Drekmeier told me. You can find out more about industrial composting in the Nitty Gritty answer.

But back to your original question: when composting truly isn’t an option, should we toss food waste in the trash or shred in the kitchen disposal? Essentially, it’s a not-great choice between clogging landfills, or stressing sewage treatment plants and potentially polluting waterways.

Given the evidence, it’s hard not to dump on landfills. The United States spends about one billion dollars a year just to dispose of food waste. In landfills, that waste releases a medley of heat-trapping gases, including carbon dioxide and methane, and plenty of foul odors, too. Kitchen disposals, meanwhile, present an alternative to landfills for most food waste, shredding it so that it can pass through plumbing and be treated along with human waste in sewage treatment plants. (Grease and oil are the exceptions—they’re too likely to clog your pipes.) On the surface, kitchen disposals seem the next best thing to composting. They have potential to recycle nutrients, conserve energy and reduce global warming emissions. But not all waste systems are created equal. Many are already pushed to capacity, or only partially treat wastewater before releasing it to the environment. And though the “biosolids” they remove from wastewater can be composted, more often they are burned—wasting potential fertilizer and releasing greenhouse gasses into the atmosphere. Sewage treatment plants also generate methane, a greenhouse gas 21 times more potent than carbon dioxide. Advanced waste treatment plants harness methane for energy production, giving them an edge over even the best landfills.

In general, the kitchen sink trumps the trash in terms of climate impact and energy use. But kitchen disposals can have more negative impacts on surrounding waterways and they use a significant amount of water—approximately one gallon per person per day.

In the end, dealing with non-compostable waste depends on where you live. In areas where water is scarce, or where sewage treatment is insufficient, the trash is the most environmentally conscious choice for waste disposal. Otherwise, the kitchen sink is your best bet, especially if your local wastewater treatment plant harnesses the methane it generates. You may be able to find your local facility on this list, but it’s not comprehensive, so you may have to call your local authorities to be certain.

Whether you’re dealing with food scraps, or paper waste or anything else, “It is very important to know the rules of where you live, work and play,” says Stanford University’s Zero Waste Manager, Julie Muir. Even on campus, she points out, 30 percent of Stanford’s landfill-destined trash is food waste. “We can do better,” Muir says.

You may not want to take on my habit of finishing other people’s scraps, but careful planning can allow you to recycle leftovers in other dishes. The best step, of course, is to produce less food waste to start with. There are plenty of tasty recipes that reduce food waste, as well as creative ideas for how to use waste you do generate. Bon appétit! Find details on reusing leftovers, and paper products best for composting in the Nitty Gritty answer.

We’ve been keeping a compost bin for several years and find it dramatically reduces the volume–and smell–of our regular trash. We collect scraps in a bucket beneath the sink and walk it out every few days to a 3x3x3-foot bin of two-by-fours and chicken wire. A shot of dirt and a quick turn every now and then and it just cooks right along. It has a nice worm colony, as well. It also helps now and then to discretely add a little human-generated waste water. A little nitrogen goes a long way.

Pingback: Monday Leftovers

Kitchen disposals only waste water if you run water specially to run the disposal. If you’d run the water anyway, the water is not waste. I run my disposal when I’m waiting for hot running water.